Early in the 20th century in the bustling neighborhoods of Chicago, word spreads that the Antichrist has been born. Using newly uncovered rare and unpublished archival material, this is the never-before-told true story said to have inspired Rosemary’s Baby.

Ben Hecht, 19, was hustling his way as a reporter for the Chicago Daily Journal. He did not have much reporting experience but had a way with colorful phrases. Here was one example: “Eyes as innocent as if they had entered their sockets a half-hour ago.” His own eyes had an intense sparkle, but his demeanor sometimes betrayed youthful uncertainty that lingered after a short, unsuccessful stint at college.

One day in September 1913, the Chicago Daily Journal’s city editor, Eddie Mahoney, called for him. Even on the sunniest days, the paper’s offices felt like “midnight,” with a few dull bulbs hanging from the ceiling. Eddie had a tip on a story that he wanted Ben to follow up on.

Ben listened as Eddie explained. The tip seemed more like a prank, but Eddie was not laughing. When he had left Wisconsin, Ben knew Chicago would be very different, a city of more than two million known at the time for frequent fires, kidnappings, auto accidents, gambling rings, and riots. Still, Ben could never have expected an assignment like this, one that charged him with entering the spiritual fray between good and evil and tracking its core combatant.

According to the tip, the Antichrist–the Devil’s child, Satan incarnate–had been born right there in Chicago.

Ben was incredulous. But journalism jobs were hard to come by, and Ben’s youth made him expendable. He had to prove himself, even if tasked with the impossible, something that seemed straight out of scripture rather than a newsroom. For the next six weeks, he would become consumed along with investigators from all walks of life, divided between those determined to spotlight destructive superstitions and those convinced they had a narrowing window of time to stop ultimate evil from being unleashed.

Clara Anderson, whose real name is not reported in extant accounts, lived on the Near West Side of Chicago. Over the decades, this formerly exclusive area had become overcrowded, now housing an assortment of immigrant communities. Clara’s daughter attended an opera at Handel Hall on Randolph Street in early April and returned with an unsettling tale. In the audience, she had spotted an acquaintance from the neighborhood, a pregnant woman. The acquaintance seemed transfixed and strangely affected by the music and performance.

“The Damnation of Faust,” subtitled a “dramatic legend in four parts,” was an amalgam of opera, symphony, and choral singing. French composer Hector Berlioz had become obsessed with Goethe’s play Faust, an archetypal story of a man selling his soul to the devil. But Goethe had loathed the idea of setting Faust to music, which supposedly generated a curse on any composer who would try. To this day, attempts to stage musical versions of Faust report mishaps, sudden illnesses or deaths, and labor strikes attributed to the playwright’s curse.

Superstitions may have factored into a longstanding reluctance to stage “Damnation of Faust” in Chicago. Newspapers pointed out that the operatic performance had not been staged in the city for 11 years, making it “a creation much talked about and rarely heard.” But if the theater and music world perceived Faust as a headache waiting to happen, it never failed to excite the public. The Apollo Club wanted to raise money to contribute to Illinois’ relief funds after a recent series of floods–later known as the Great Flood of 1913–had plagued the Midwest and became one of the deadliest series of natural disasters in American history. To help those beset with tragedy, the organizers sought the popular appeal of Faust despite the tragedies associated with it.

The performance at Handel Hall opened on April 7 to a capacity crowd of approximately 520, raising thousands of dollars for the flood relief fund. In Berloiz’s version of the iconic story, Méphistophélès, a demon, ultimately ferries Faust directly to Hell, a scene staged in detail considered shocking. To some observers, audience members weren’t merely entertained but spellbound. The Chicago Tribune described the opera’s “curiously fantastic spirituality.” At the same time, another newspaper’s critic noted that the audience “seemed to be a bit dazed by the work” but “responsive,” an incongruous combination suggesting a kind of mass hypnosis.

In particular, the pregnant woman, as recounted to Clara Anderson by her daughter, seemed mesmerized, as if the performance triggered some profound fear or realization in her. Other neighborhood reports offered darker details of the distressed woman and her pregnancy. In one strain of accounts, the expectant mother already had six daughters, and her husband ranted that he would rather have a devil in the house than another daughter. As if to make his point or compelled by a force he could not control, he set about destroying various religious objects around the house. Adding to the intrigue was information that the woman had been having an affair. In another variation, it was the pregnant woman herself, after the strange impact of the opera, who declared that she would just as soon have a devil as another baby.

Six months after the opera opened, the woman went into labor at home. The room went dark, according to accounts, and then a strange red light briefly appeared to shine. When the baby was born, the father was said by some to have an abrupt, extreme reaction. In this version, he was a “sensitive, pious man, and sank to his knees and prayed” after sensing something wrong. He called out, “Great God, why have you done this to me?” Suddenly, he picked up a club and raced toward the child before he stopped short, “spellbound.” Depending on the version, the father then fainted; others reported he died on the spot.

Clara’s daughter told her that a nurse there to help the family whisked the baby out of the house, possibly to protect the child–or, even stranger, to protect the family. Disturbed and confused by the accounts she was hearing, Clara decided to find out where the newborn had been taken and why.

On a mission to impress his editor, Ben Hecht tracked down every bit of information he could find on the story. Determined to be taken seriously, he hit the streets with an excess of style, decked in a suit, black tie, and slanted fedora, with a close-cropped mustache. He had every reason to expect people to laugh at his questions. But they did not. “Scores of people” around the city, he later remembered, knew precisely what he was talking about when he brought up the strange tale. Some were too nervous to speak, but others offered details. The basics boiled down to the facts that the baby was born in Chicago in mid-September, delivered by a midwife, and identified by various authorities as demonic before being taken into hiding. Another fact became clear–priests and other members of the clergy were now searching the city for the baby, suggesting they knew more than what Ben heard on the streets.

Ben’s reporting led him to the Near West Side– the same area of Chicago where Clara Anderson also heard the events had transpired. The reporter’s legwork narrowed down the location to Galt Court. This neighborhood was primarily composed of Italian immigrants, with surrounding areas that boasted Irish and Jewish residents. This locale created a snag when interviewing informants and witnesses to learn more: Ben did not speak Italian. He needed someone trusted in the community. He contacted a boxer named Joe Govani, who agreed to contact some Italian residents he knew. Meanwhile, Ben surprised himself at how much he had begun to obsess over the story. His desire to find more became a burning need to know what happened.

After three days of reporting, Eddie Mahoney called him in. Ben prepared to give his editor an optimistic update, but he was surprised, then stunned, by what Eddie had to say. The editor was shutting down the story. Eddie explained he worried the reporting could “warp [Ben’s] mind.” The situation was confusing. Ben hadn’t brought the tale to Eddie; it had been an assignment. Frustrated, Ben sought a second opinion from the newspaper’s sports editor, Sherman Duffy, whom he considered a mentor. Sherman was blunt, often giving kernels of thoughtful, colorful advice. Ben would later remember him imparting this pearl of wisdom: “Socially, a journalist fits in somewhere between a whore and a bartender, but spiritually he stands beside Galileo. He knows the world is round.”

Ben Hecht

Ben recounted to the sports editor the oddly convincing, detailed accounts he had been gathering. But Sherman was a realist about why the paper pulled the rug out from under Ben’s strange new assignment. Sherman took the side of his fellow editor. “If you want to believe in a myth, well and good, but don’t use your legs trying to verify it. Myths are for churchgoers, not reporters.”

Ben knew deep down he should listen to his editors, whom he considered the “wisest” people he knew in Chicago. But he couldn’t let go. On one level, Eddie Mahoney’s complete turnaround was mystifying, especially for a story that could sell papers, and seemed to demand another explanation. On a broader level, there was a sense that people’s stories were discounted because they were considered ignorant and unworthy. Ben’s parents had emigrated from Belarus. He knew well the temptation to dismiss the Old World–he had felt compelled to distance himself from his Jewish and Eastern European heritage.

In addition, something strange seemed to be in the air as the story of the Devil’s Child spread; events around Chicago appeared to possess a cosmic connection and meaning as if adding up to an omen or sign. Advertisements went up around Chicago for a lecture entitled, “Will Satan Ever Die?” “It is only reasonable,” the lecturer told his audience, “to conclude that the Creator would not form a being which he himself could not destroy if such action was found necessary.” Around the same time Ben was racing through the city on the trail of the Devil’s Child, a furnace at a tractor factory on Fullerton Avenue inexplicably overheated, sending up waves of heat and fire so intense that the giant chimney fell off, entombing one man in bricks, killing him and severing water pipes that almost drowned two others. Two days later, an unexpected gale from the northeast created an atmospheric shift so rapid and extreme that the temperature suddenly dropped 40 degrees.

Even without his editor’s approval, Ben certainly could not be blamed for taking a walk from the Journal’s Market Street offices to check out Handel Hall, the site of the Faustian performance said to trigger the peculiar response. Maybe there were clues left behind, people who could remember particulars about the performance that night or its attendees. But all Ben would find left of that theater was rubble. Weeks after the performance, the building, which had been a fixture in the city for decades, was torn down.

When Ben was back in the Journal’s newsroom, one of the phones rang for him. It was the boxer Joe Govani, and he had news. He had gathered a list of midwives most likely to have delivered a baby in Galt Court. Ben should have thanked Joe and apologetically told him the editors had killed the assignment. Instead, Ben asked Joe to tell him everything.

In the Near West Side of Chicago, the landscape of Catholic churches and Jewish synagogues lent an Old World atmosphere. In the amalgam of spiritual traditions carried over by recent immigrants, there existed vigilance against a perceived erosion of faith and subversion of godly values, especially as more established residents urged assimilation. In the push by immigrants to retain older belief systems, there was a high alert against a turn toward evil.

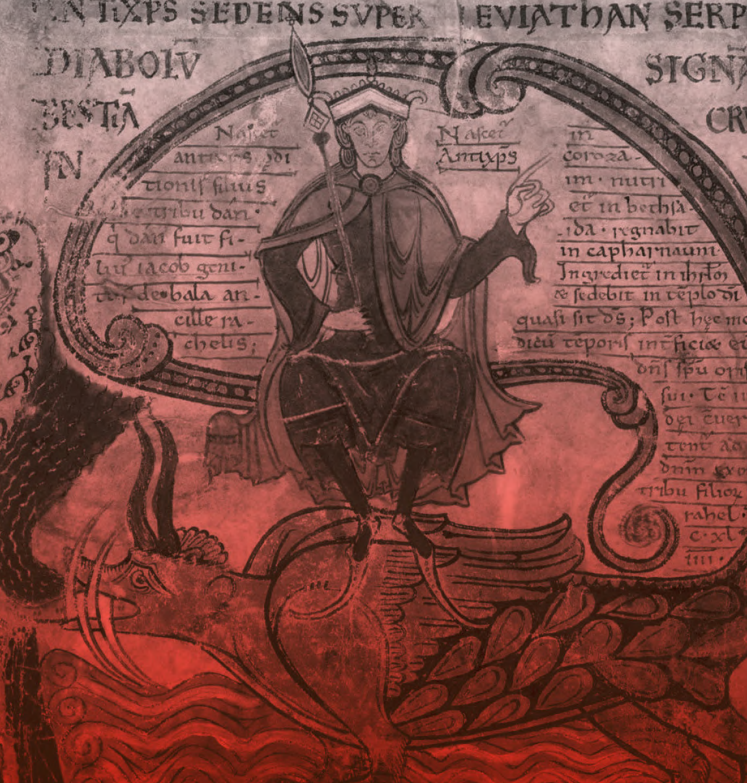

Medieval manuscript on the Antichrist

According to these traditions, the ultimate harbinger and purveyor of darkness on earth would come in the form of the Antichrist or, in Jewish texts and lore, a kind of anti-messiah. “As the Son of God in His human birth manifested His divine nature,” wrote 4th-century scriptural commentator Ambrosiaster, “so also shall Satan appear in human form.” Interpretations of ancient texts zeroed in on the Antichrist coming to power from an obscure place, the “furthest bounds” (as described by early Christian theologian Lactantius) of the known world, or a kind of Babylon. Another prediction appears in the Book of Revelation 17:9-10: “There are seven kings. Five have fallen, one is present, and one has not yet come. When he comes, he must remain for a short time.” This was interpreted as a clue about the Antichrist. As an inverted version of Christ, rather than being born of the “immaculate” Virgin Mary, the Antichrist would be born to a woman who was not a virgin, a woman in troubled circumstances. Tenth-century Benedictine Abbot Adso of Montier-En-Der interpreted scripture to indicate the Antichrist “will be conceived wholly in sin, will be generated in sin, and will be born in sin.”

Though Judaism did not conceive a hell, demons proliferated in scriptural lore and the Old Testament. Among Catholics, fear of the Antichrist extended to the highest levels of the Church hierarchy in the early 20th century. The preceding Pope, Leo XIII, was seen by witnesses becoming “pale and fearful” during a Mass. He revealed later that he had experienced “a vision of demonic spirits.” He was shaken by the occurrence and bolstered the Church’s theological bulwark against demonic forces. The next Pope, Pius X, who was in office when the story of the Devil’s Child began, foresaw that the present era could expedite the path for the Antichrist. The “disastrous state of human society today” fit with the timing and conditions for the Antichrist, causing Pius to warn that “there may be already in the world the ‘Son of Perdition.’”

Meanwhile, the Church’s local authority in Chicago was the city’s archbishop, James Edward Quigley. He spoke multiple languages and advocated for immigrant communities. Increasingly, Quigley focused on urging the youth to “look after” their faith. The stocky, 59-year-old leader publicly entreated Chicago’s youth to redouble their efforts to keep their faith “pure and strong” because the time had come to harness the “power to resist evil.”

If the Antichrist indeed were to appear and was not contained, theological thinkers believed it would signal displacement of religious belief and a rapidly crumbling reverence to God that would lead to worldwide suffering and, ultimately, the final days.

In addition to the improvised searches that had begun, official investigations were initiated at the highest levels of Chicago society.

One of these inquiries fell to Captain Thomas F. Meagher, a 23-year veteran of the police force. Meagher was known as a straight talker and “an honest police officer,” as reported in a local paper. He had emigrated from Ireland when he was 17. His supporters praised him for cleaning up a Chicago district riddled by all-night saloons, gamblers, thieves, and corruption. For the same reasons, Meagher was despised by crooked cops, whose vendettas against him were conspicuous enough to make the news.

Meagher, 49, would smoke “good cigars in placid content” in his office as he plotted his approach to cases. Though records of how he started the investigation and why have been lost, what remains indisputable is that Meagher was searching earnestly for the Devil’s Child.

Police Captain Thomas Meagher

In the meantime, a pair of private detectives were hired to open an investigation. The best candidates were Joseph H. Schumacher, superintendent of the Chicago offices of the Pinkerton Detective Agency, and his assistant superintendent, Hugh McCaffrey. Schumacher, 50, had pursued some of the later Wild West bandits along with his brother Charles, who was then killed in a 1903 shootout with associates of the Younger gang.

Schumacher wore a “fierce demeanor” and was known for some of Chicago’s “slickest pieces of detective work.” In an age when most people walked or took public transportation, he would roar around Chicago in his car, pulling up to the curbs to demand answers from suspects and witnesses. He often worked closely with police and insisted that with their combined efforts, “Chicago is not now the wickedest city,” despite its reputation.

In addition to other similarities, the start of these investigations by Meagher and Schumacher was shrouded in mystery. The identities of who ordered the police search and who hired the detectives remained undisclosed, but whoever was pulling the strings of the two investigations had to be powerful Chicagoans.

Regardless of who activated them on their searches, Meagher and Schumacher put their heady reputations on the line by looking for the Devil’s Child. In essence, a citywide race was on, and everyone else looking for the Devil’s Child was put on notice–the finest investigators in the city, men who were no strangers to violent confrontations, should not be crossed or obstructed.

Ben Hecht wasn’t just undertaking a high-risk, high-reward career move chasing the story. He also had to admit that his investigation grew rapidly into “an almost hysterical belief” that something supernatural and devious was happening, which came with a responsibility to help expose it. He met up with Joe Govani. O’Connell’s Gym, on South State Street, was the place to be when it came to boxing in Chicago. Punches thudded the thick, drooping speed bag against the wooden frame while thicknecked boxers heaved a medicine ball back and forth. Joe, an ambitious local lightweight, weaved in the ring. Short but solid, he was quick and could take a punch, but was somewhat rough around the edges. His trainer, Bill “The Professor” O’Connell, would pause the sparring matches to give instruction.

Joe recounted his progress to Ben. The boxer had identified the midwives who recently helped expectant mothers at Galt Court. In Chicago, midwives handled nearly 50 percent of all births, particularly in the immigrant communities. Armed with Joe’s information, the pair traveled to talk to each woman on their list. They visited cramped apartments and family-owned stores. Ben would ask questions that Joe would translate and convey to the potential witnesses; then Joe translated the answer for Ben. Even without understanding the language, Ben could read the mixture of fascination and fear in the faces of the people they visited.

It was a slow process, and Ben had to be careful that his work was discreet. He had gone rogue by defying his editors’ orders and continuing to investigate. On the other hand, if Ben succeeded in finding the truth, his career could reach new levels. With the stakes escalated, he felt himself becoming a “bloodhound” on the trail. All the accumulated reporting pointed to one place: Hull House, a social work hub helping the immigrant community. The leaders at Hull House denied all of it, practically laughing at the allegations. Still, pressure and intensity mounted. Ben could judge the seriousness of the situation by the growing number of searchers. There were the other Chicago reporters pounding the pavement, of whom Ben had to stay a step ahead. Then there were the clergy from the Church, who were also looking all over the city, and now the police and private detectives.

The Catholic priests, unlike Ben, possessed a veritable guidebook to the Antichrist that went back centuries and could be cross-referenced with the present situation. The mother was said to have six other children–fitting the scriptural prediction of the Antichrist being a “seventh king.” The Church also had compiled lists of physiognomy that the Antichrist would uniquely possess–matching up with accounts told to Ben of the Galt Court baby having long hair and a complete set of 32 teeth (an impossibility for an infant or child). Further, the supposed affair by the baby’s mother fit with ideas of the Antichrist being conceived in sin, while the criteria of coming from obscurity and a kind of Babylon–a chaotic and fragmented city–matched these neglected sections of Chicago.

Important people seemed to want to stop the search or keep the search results to themselves. Ben had to look no further than his editor’s sudden reversal that killed his assignment. Having Joe by his side as he crisscrossed Chicago didn’t just give him language skills; it also gave him protection from anyone in their way.

If Ben couldn’t entirely explain his compulsion to find answers in the case, Clara Anderson and other searchers adopted a clear-eyed sense of responsibility. Those convinced that the Antichrist was being hidden somewhere in their neighborhoods felt they were on the front lines to stop the world’s spiritual ruin. But for these believers, there was a short window of time before the era of evil would begin. If they could find the baby, a baptism could disrupt his identity as the Antichrist. The searchers’ desperation reflected a fear that the child would be smuggled away from the city at any moment, never again to be traceable. For the faithful, part of their terror came from the scriptural interpretation–dating to Saint Ephrem in the 4th century and the rare, undated Greek Apocalypse of Ezra–that the Antichrist would be born a shapeshifter so that even recognizing it would become more challenging as its powers increased each passing day. Moreover, in Catholic belief, only baptism that occurred soon after birth would have a strong enough effect to have a chance to counter this radical circumstance. If the searchers were right, quick action was the only chance to save the baby and the world.

Though lacking a reporter’s training and resources, Clara Anderson had the expertise that came with being part of a tight-knit community. With access to neighbors and area merchants who would not always willingly speak to authorities or journalists, she followed her leads, discovering that the nurse who took the baby brought it to Hull House. Hull House was a woman-led space where impoverished immigrant families could benefit from the guidance of progressive and talented women. Clara also had a contact there. Her neighbor was Hilda Polacheck, 28, a Polish immigrant and one of the lead activists for Hull House.

Hull House

Hilda later remembered how Clara “implored” her to use her influence with Hull House. The fact was, many people heard that Hull House had taken in the child. A few inquiries became dozens, then hundreds, then thousands. Some of the inquirers were penniless; some were very wealthy. In the latter camp, “they were willing to pay any price that Hull House might want to charge,” Hilda recalled, to be brought to the child. Most of these searchers carried no world-saving ambitions of those on a quest like Clara’s. Instead, they seemed irrationally transfixed, like the audience to the Faust performance, desperate for a glimpse of the Deil’s Child. The public demands worked their way to Jane Addams, the founder and director of Hull House. Jane and Hilda patiently refuted every story about Hull House’s involvement with the so-called Devil’s Child. They framed the reaction as a kind of mass hysteria and a dramatic example of the unfortunate ignorance and superstition that came with the immigrant communities they served.

As word spread of Hull House’s alleged involvement, so many people called on the phone and showed up at the door that the organization had to suspend operations.

Clara, confident that Hilda’s intervention was the best hope for the child and humanity, was frustrated when Hilda came back to her to insist there was no such child at Hull House. Clara lost her temper, cursing her neighbor. In Clara’s eyes, Hilda and the Hull House leadership were failing the community they served in a way that would have catastrophic consequences.

Tales of the events, including the connection to Hull House, reached every corner of the city, including the “poor houses,” subsidized residences for the impoverished and elderly. Inside one of these, an Irish resident described by observers as an emaciated, “crippled old woman” with “misshapen hands” had a memorable reaction when she heard about the child. She was “seized” with an interest that went beyond the curiosity overtaking some many. Her reaction came close to obsession. The poor house was in a remote location of the city. Hull House may as well have been the other side of the world for the woman, but her obsession turned into a desperate need to get there.

The older woman made cryptic statements that left witnesses guessing at the source of her preoccupation. She spoke about her grandmother in Ireland having a “second sight,” a supernatural clairvoyance. She explained that the women in her family inherited a capacity to communicate with the banshee, a spirit in Irish legend who served as a messenger from the afterlife.

To some, the older woman appeared to imply she was related to the baby. More generally, she insisted on a spiritual link to the child that required her, despite being infirm and poor, to either save or guide him. This called to mind Adso, the Benedictine abbot who had influenced almost all scriptural interpretations of the Antichrist. “The Antichrist,” Adso wrote, “will have magicians, enchanters, diviners, and wizards who at the devil’s bidding will rear him and instruct him in every evil, error, and wicked art.” With full conviction, the woman appeared to insist she was one of these guardians.

As days passed, the older woman became more agitated, in agony, it seemed, to be apart from the child. According to one witness who met her, she “lay awake nights figuring how she could get” to the baby. She slipped out of the poorhouse one morning and crossed the street to a saloon. There, she pleaded with the bartender to help her get across the city, telling him she had to get to the child. The bartender helped walk her to a streetcar, paying his dime for her fare. He and the streetcar conductor lifted her into the vehicle.

Clara would not give up. A few area residents decided to join forces, identifying the location at Hull House of a child fitting all known descriptions. The group had a plan. Most details of this joint effort have been lost, but newly surfaced archival documents claim they managed to get a hold of the baby at Hull House, smuggling the child out in a shawl and rushing away into the streets of Chicago.

As for the older woman from the poorhouse, she was on her slow odyssey through the city. Once the streetcar approached Hull House, she stepped down, worn out. She struggled as she practically dragged herself to the Hull House entrance. The organizers at Hull House, including Hilda Polacheck and Jane Addams, who had been busy dismissing searchers by the dozen, were struck by this visitor more than any other. They stopped everything they were doing and sat down with her. They brought her a tray of tea and cake, hoping to get her to talk. Hilda took note of the woman’s unusual intensity when she spoke about the Devil’s Child. “Her whole being seemed to be lifted to a higher plane.” The woman pleaded to see the Devil’s Child.

As for Captain Thomas Meagher, his investigation had continued to progress, possibly in direct collaboration with the Pinkerton detectives. The clues pointed them to an address at the north end of Douglass Park on the West Side, which was the possible location of the hidden child. By this point, there were so many searchers after the child, with so many motives, that the investigators could not know what to expect. Earlier in his career, Meagher had to raid a house holding men wanted for armed robbery; while Meagher questioned one of the residents, one of the other police officers was shot and killed. Meagher and the others showing up at Douglass Park would be well-prepared and well-armed. But they found nothing there, leaving them stumped.

The group with the baby, keeping him wrapped tightly in a shawl, rushed him to a church. In this case, the Catholic tradition of baptism involved a priest acting in persona Christi, or in the person of Christ, as a way to expel evil. “Baptized in the Holy Spirit,” a phrase from the Acts of the Apostle, had to be channeled and called upon to act.

Holy Family Church

The Church of the Holy Family was a sweeping Victorian Gothic cathedral whose tower was the tallest structure in the city up until 1890. Boasting the oldest stained glass in the city and an altar built by a German master carpenter, the architectural marvel survived the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, earning it the title of “The Miracle on Roosevelt Road.” For all its grandeur, “nickel and dime contributions” from its poor, devoted immigrant parishioners had funded the church’s original construction. It symbolized faith, strength, and immigrant unity and the perfect setting for what the group hoped would be another miracle: deliverance for the child and humanity.

With so many chasing down leads on the child, the group had to guard against the intrusion of reporters, law enforcement, and church authorities. The small group had to keep guard at the church’s doors to protect their plan. But when the priest came, they unwrapped the shawl to find it empty. They later reported hearing a faint laugh ring through the church and never saw the child again.

At the tense tea party with the mysterious visitor at Hull House, Hilda and Jane insisted to the older woman that there was no Devil’s Child, dismissing the entire concept as myth. As Jane would explain to others, she viewed the “fairy stories” as being invented by “primitive women… to influence to gentler ways their brutal lords and masters.” Over the last six weeks, Jane had become frustrated with the endless parade of “ignorant inquirers.” But even the two Hull House activists, who professed complete skepticism, were struck by this woman’s “proprietary interest” in the Devil’s Child. They gave her money for her ride home, but she did not want to leave. The woman, already drained physically and mentally, seemed emotionally crushed. She sat at Hull House, hands trembling in her lap, mumbling strangely to herself or possibly reciting an incantation.

Word spread that the last hope for the situation to be reversed or controlled had failed. Residents of the area headed for their places of worship. Ben Hecht witnessed this as “the hellish infant” vanished. “The churches filled up,” he noted, “with people praying to be spared from its evil.” Ben wandered into one of these cathedrals. It was filled with “candle-lighted white statues” with “a host of men and women murmuring on their knees,” praying that the worst would not come.

The final traces of the child in public reports coincided with Halloween night, adding hints of pagan chaos to the ancient religiosity that had informed the panic and search. To those who believed in the hunt’s urgency, an evil had escaped that may not have been stoppable, and they could point to a bloody ripple effect. That night, a 15-year-old boy felt compelled to climb to the top of a light pole, electrocuting himself. The teen fell dead to the ground. Elsewhere, a false fire alarm rang out, the fire buggy running over and killing a young man.

Within seven months, the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand triggered WWI, ushering in a new scale of violence and destruction and ultimately paving the way for a brand of mystical fascism that would, in turn, empower another global war.

Hull House’s Jane Addams continued her prominent role in groundbreaking social work, including founding the American Civil Liberties Union. By critiquing the stereotypes carried over from Europe, the Hull House leaers projected their stereotypes of immigrant women as superstitious, uneducated, and fanciful. Despite her professions at the time of the Devil’s Child, as it turns out, Jane Addams sincerely believed that Hull House was haunted and possessed a supernatural presence. Jane insisted that she and others in Hull House, including Catholic nuns, saw a woman in a rustling dress–not unlike the Irish banshee of the enigmatic older woman from the poorhouse–floating through the rooms. Some inhabitants left pitchers of water in strategic positions based on the belief ghosts could not cross running water.

As it turned out, the mysterious source of funding for the private detectives had been Jane Addams and the Hull House leadership all along. Jane slipped up and acknowledged this a year after the events, saying, “We put the detectives to work” during a lecture on the Devil’s Child events. She never mentioned that fact again over the following decades, despite repeatedly lecturing and writing about the Devil’s Child events. Though the baby’s gender was not reported, Jane also specified the child was male. At the same time, in later retellings, Jane changed the detail of the expectant mother having six children and the new arrival being the seventh, bumping up the number to seven previous children and dislodging the correspondence to the “seventh king” scripture. In private correspondence, Jane admitted that the Devil’s Child phenomena “threw me off.” The question remains what Jane wanted the detectives to find. Because Hull House in 1913 comprised 13 properties that extended the equivalent of a city block, it could well be that the Hull House leadership suspected someone was hiding a child–or, skeptics would claim, knew a child was being hidden, possibly losing track of it within the organization’s properties. The Hull House leadership acknowledged that their operations had to shut down because of the Devil’s Child. Still, in addition to fending off the crush of attention, this pause in their usual work may have been used to organize their efforts related to the mystery child.

Speculation ramped up that the child had been moved to an isolated retreat in Waukegan, Illinois, at a compound owned by Hull House. Others have insisted that to this day, they can spot a spirit figure of a child staring out from the attic window of Hull House. In the late 1990s, the Dayton Daily News reported that four monk-like spirits wandered the Hull House’s rooms, in addition to “an inexplicable, glowing ectoplasmic mist” that the paper claimed had even been captured on film.

Jane’s ambivalence came out between the lines of the straightforward sociological analysis she composed about the Devil’s Child. During World War I, President Woodrow Wilson took time to pen a private letter to Jane praising one of her published recollections of the events surrounding the Devil’s Child and noting that it stayed with him. “The pathos and revelation of it all are indeed poignant and I carried away from reading the article what I am sure will be a very permanent impression.”

In the weeks after the child vanished from the city, a teenager showed up at the East Yards police station in South Chicago, explaining that he had followed “the devil’s order” to kill his father, leading them to their home on Avenue M, where his father’s body, wrapped in a sheet, was in a wheelbarrow. “The devil told me to carry my father’s body down to the river,” he explained calmly. “I went out and got the wheelbarrow… Then the devil went away and I came over to see [the police].” Weeks after that, in Moline, Illinois, a 42-year-old man reported that he had been “sold to the devil” and hanged himself on the rafters of his woodshed, days before a 26-year-old traveling through the midwest killed his family, insisting “I seen the devil. I have seen him many times. I seen him in [my wife’s] eyes,” also telling police he was a “magician” known as “Willard the Wizard.”

For those who had believed they had come close or crossed paths with the Antichrist, they expected the child and his “magicians, enchanters, diviners, and wizards… his constant associates, and inseparable companions” would remain in hiding until his time came to ascend. Twelfth-century monk Joachim of Fiore commented on this, describing a mirror image of Jesus: “Because Jesus Christ came in hidden fashion, Satan himself will do his works hiddenly, that is, signs and false wonders will be designed to seduce even the elect if possible.” That it had all happened in 1913, with the search focused on the 13 properties at Hull House, called to mind the Last Supper hosting 13 guests on the 13th of the month, and Judas being the 13th apostle to Christ, the numerology also echoing society’s more general superstitions of the number 13. For immigrants and those of foreign descent, to have such beliefs dismissed as supernatural rang shallow in a world where millions openly believed in Christ’s immaculate conception and a nation built on claims of divine rights.

Shortly after the search for the Devil’s Child, having been hailed as a future lightweight champion, boxer Joe Govani disappeared into anonymity. Ben Hecht never published the newspaper report on the Devil’s Child that he worked on with Govani, though Ben always remembered the details of his search, revealing some of them shortly before his death. Over the years, as he transitioned into a successful career as a playwright and screenwriter, Ben began to renew his interest in his Jewish and European roots.

As a playwright, Ben went on to write plays staged at Hull House Theater, which Jane Addams had established as part of her contribution to the community. Interestingly, Addams converted an area of Hull House, considered an epicenter of its hauntings, into a storage and dressing room for the performances. Actresses changing in the room claimed that the door would lock and a “strange lady dressed in white [sat] on a box looking at them.” Once, a group of actresses rushed backstage and said they would never return to that room again.

Whispers about the Devil’s Child lore were said to have inspired the novel Rosemary’s Baby, considered a definitive work of modern horror. Ira Levin, the author of the novel, may well have heard details from Ben Hecht himself, as their playwriting careers in New York overlapped, with both headlining productions that opened in the same Broadway theater (Ben died before Rosemary’s Baby was published). The film adaptation of Rosemary’s Baby was said to be cursed, with a theory that Roman Polanski had sold his soul for its success, not unlike its character Guy Woodhouse or the archetypal character of Faust, that doomed protagonist of the “Damnation of Faust” operatic performance said to have cursed Chicago. Rosemary’s Baby and its cinematic progeny, The Omen, zero in on the contours of families’ experiences with children whose destinies they feared. The true story of the Devil’s Child that preceded these fictional versions has a more expansive scope, incorporating a cross-section of society that interacts and reacts to the supposed presence of the antichrist. The dual horror of the true story comes from the establishment’s fear of the beliefs of lower socioeconomic and immigrant cultures and the immigrant population’s fear that the powers-that-be would ignore them until evil spread beyond containment.

Traces and rumors of the child faded with time. In 1916, the Rock Island Argus, a newspaper based two hours outside Chicago, published a classified ad. The ad, slotted between a request to buy a coal stove and a home for rent, ran around the time when the vanished child would have been celebrating his third birthday. Placed by someone looking for funding, it included a mysterious message.

WANTED—Partner with $25 for the greatest freak of nature ever born—the devil child.

It is unknown if anyone responded.