Their cell phones were supposed to keep their families safe and connected. Then the technology was taken over by someone bent on tearing them down. Was it all a social experiment, a warning that if we failed to control our phones, our phones will control us? The untold true story.

SOME NAMES AND OTHER IDENTIFYING DETAILS HAVE BEEN CHANGED OR WITHHELD FOR PRIVACY REASONS.

IN EARLY JUNE 2007, at her house on Fir Park Lane, Heather Newhouse, 38, waited for the installer to finish setting up the alarm system. As suggested by the street name, fir trees dot the neatly cut lawns here, as though the neighborhood remains in a permanent Christmas. Blue eyed with straight blonde hair, Heather, one eye on her cell phone, appeared like any other multitasking working mom in the suburb of Fircrest. But the voicemail on her cell phone revealed turmoil.

I can’t wait ‘till you die. Oh my gosh. You will all be dead, even the officers.

The voice was guttural and scratchy, seeming to relish the reference to the police officers she had begged for help.

For months now, Heather and her family had been harassed—more than that, stalked—by someone who seemed to see them at all times and know everything about them: what they were doing, what they were wearing, what they were saying.

Fircrest, Washington

No one seemed safe from the surveillance and menacing: not her once carefree children, not her elderly parents, not even the baffled law enforcement officers. “Never in a million years,” Heather said, “would [I] have dreamed that something like this could have happened to our family.” She tried to be strong even as she reached her breaking point. Frightened by the threats, overwhelmed by the fact that everyone could be a suspect, Heather and Tim, her husband, had ordered the security system at their house.

Installation completed, the security system represented a new peace of mind, just as the alarm companies advertised. The Newhouses set the system to engage—and then Heather got another call.

The phone screen read: Restricted.

It was happening again.

The Newhouses, along with dozens of other families across Pierce County, Washington, were the victims of sustained and sadistic technological torment that defied explanation. One of the central investigators of the case, a mobile forensics expert with 30 years of experience, has said a case of this complexity and magnitude not only had not been seen before, but has “never happened again.” At a formative time in mobile communication, as new devices transformed how people connected with one another, technology itself seemed to turn against a community, injecting terror and mistrust. With unprecedented access to police reports from multiple departments, victim testimonies and evidence, Truly*Horror can now tell the full story of the case that sent fear rippling through families’ homes, the public school system and the local media, while also confounding multiple police departments, the FBI and Homeland Security.

Hand trembling, Heather answered the phone. The unknown Caller, voice distorted, replied.

“3-7-2-1.” It was their alarm security code.

A HALF-HOUR SOUTH of Seattle, the Puget Sound winds around greater Tacoma, where snow-capped Mount Rainier hulks in the distance. The largest city in Pierce County, Tacoma was surrounded by residential suburbs like Fircrest, a close-knit town founded by Edward Bowes, a San Francisco investor who later hosted the most popular radio show of the 1930s. When a single police officer’s job was on the chopping block during budget cuts in 2007, the community reflex was to resist. “Law enforcement is a true necessity in Fircrest,” the mayor said. “It protects the quality of life we have.”

Across the Tacoma Narrows Bridge, on the Kitsap Peninsula, lies Gig Harbor, a once quaint fishing community with a burgeoning retail expansion that was modeled after Seattle’s University Village. Past the marinas and Route 16 is Gig Harbor High School, which stood in front of one of the many forests that pepper the expanses of the county. Fircrest and Gig Harbor are a far cry from Tacoma proper and the pockets of crime with which it struggled. One police officer commented that the area of South Tacoma Way was rife with “any kind of gang that you can think of.” Local police even sponsored a series of neighborhood summits titled “Basic Gang Recognition” on Thursday nights. In January 2007, a student at Foss High School in Tacoma shot another student at point blank range in the middle of the school hallway while students walked to first period classes.

Suburban residents worried about crime creeping into their enclaves. A Pew Research Center study released the previous year found that nearly three-quarters of Americans reported they had been kept safe by mobile phones in emergency situations. This helped expand the market, swaying adults to buy them for their older children.

By the winter of 2007, Courtney Newhouse, 15, blue eyed and blonde haired like mom Heather, was a popular sophomore at Curtis High School, also Heather’s alma mater, and part of the generation coming of age with mobiles phones. The well-liked, churchgoing Newhouse family also included Courtney’s father, Tim, 39, who was college sweethearts with Heather at Washington State University, and their younger children, Katie, 10, and Connor, 9.

Life started going sideways on February 10, 2007, a Saturday night. Courtney was staying over at a friend’s house when she received a text from another Curtis High sophomore.

“Who is this?” he texted.

It didn’t make sense. She hadn’t texted him that night, but they did text often, so he would have recognized her number.

“What are you talking about?” she responded.

He wrote back that she had texted him a slur. Courtney hadn’t, nor would she. She didn’t know what to make of how the text could have appeared to come from her phone.

At 4:21 a.m., Heather and others received calls that showed they came from Courtney’s phone. Courtney was asleep.

The next few days were full of strange calls and messages, soon documented by the Tacoma police department.

Calls from “Blocked ID” flooded the Newhouses’ cell phones and home phone. Courtney received texts to call unfamiliar numbers. She received voicemails containing “heavy breathing” and obscenities, along with others that instructed her to call her own home phone number. The raspy voice was clearly being distorted or manipulated, at times made to sound like an “old man,” at other times like a girl. Calls and messages were also made to Darci Sayer, 44, Heather’s sister.

The family went together to the Fircrest Police Department to report the incidents as “the girls were scared and freaked out.” After they returned home from speaking with an officer, Courtney received another voicemail. When she played it, they were stunned. It was a recording of them while at the police station.

Other locals began experiencing similar harassment through their own phones. One woman heard her own voice echoing throughout her house and soon discovered that someone had recorded her voice and was playing it through her home phone answering machine. This occurred four times in just one night.

The father of another victim, Jenny Copeland, called T-Mobile from her phone to report harassment and to request a new number. Jenny’s father told the representative to call him at his office, but Jenny stopped him before he could give the number.

“Don’t say it out loud.”

“Why?”

“They are listening to [the] conversations!”

Johnny Pagel, 16, also received calls at his family home in Lakewood. His mother Sue was startled that the Caller knew “what they were doing and who they were calling” even though they were inside the house. The perpetrator “even knew when [Johnny’s] friends called the police about the phone calls.”

At 6:13 pm, on Thursday, Feb 15, Heather Newhouse answered a call from someone whose voice resembled a “deep whisper”:

You guys are shit.

Two minutes later, the same voice left a message on the Newhouses’ home phone.

Heather, Courtney, Tim, Katie, Connor. You will die on February 20th.

GERALD “WAYNE” BUCK, 71, had been a cell phone skeptic and was still getting used to his Sanyo SCP-8400 flip phone. His daughters, including Heather Newhouse, thought it safer for him and his wife to have them. But they sometimes seemed more trouble than good.

Wayne had been married to Judy, 67, for 45 years. Nearly 700 people attended their wedding reception, during which the fathers of the bride and groom posed holding empty pockets and an empty wallet for a News Tribune photographer. The paper noted that the marriage “united two prominent families.” Both went to Stadium High School and graduated from the University of Washington.

Wayne owned and managed Buck & Sons, a tractor company, for 25 years, had worked as a real estate agent, and ran for several local government offices, including Pierce County Assessor-Treasurer, a race he lost despite a glowing newspaper endorsement. Life had slowed since then. Sporting a white mustache and Seattle Mariners hat, he enjoyed time with his grandchildren.

Which made it all the more distressing for Wayne when he “started receiving strange [voice] messages” on his phone. As he told the investigating officer a few days later, the calls from a “private” number quickly went from strange to threatening.

I am going to kill Ike and Plumpy.

That threat unnerved Wayne. He loved Ike, their calm black lab, and Plumpy, their calico cat. In fact, Wayne had been talking to them while feeding them right before receiving the message. It was as if someone was watching and listening to him.

He contacted Sprint, his cell phone provider. Their response was confusing and impossible: the calls came from Judy’s phone.

Wayne didn’t buy that explanation for a moment. Judy was with him the whole time. She was not using her phone when he got those calls, and the voice certainly wasn’t hers. Judy’s phone also seemed to be going haywire. Her text messages were mysteriously disappearing, deleted by some invisible hand one by one.

Wayne and Judy compared notes with their daughter Heather. The Newhouses had spent a terrifying February 20, dreading something awful happening as warned. Nobody was hurt, but the threat worked in a different way, paralyzing them. Together Wayne, Judy and Heather met with Officer Wendy Haddow on Tuesday, March 6, at the Tacoma Police Department. Heather was armed with the documentation from the Fircrest Police. While they described the various events, Heather’s cell phone received a voicemail:

Get out of the Tacoma Police Department, there is going to be a shooting there.

There is nothing quite like a threat to a police station to set off a chain reaction of frantic precautions. Officer Haddow told everyone present to remove the batteries from their cell phones.

TAYLOR SHAW, 16, light brown hair and clear blue eyes, went to a different school from her across-the-street neighbor Courtney, but they were good friends.

Taylor heard about the bizarre harassment. Courtney had shown her the texts and played the voicemails. Taylor’s family believed strongly that the younger generation should keep up with technology. Back in 2000, Taylor’s mom, Andrea, led a fundraising project at Whittier Elementary School to get 21 new iMac computers for the students.

Now, as their neighbors struggled with harassment, Andrea, 44, was cutting limes on her kitchen counter. She got a voicemail:

I prefer lemons.

A burst of unwanted texts ballooned their cell phone bills to nearly $1,000 in a single month at a time when cell plans were commonly billed by data usage with steep overcharges. Andrea, who taught at a school in the Peninsula School District, went to Gig Harbor High School, where Taylor attended, to meet with the school’s principal, Greg Schellenberg, and the police. A Gig Harbor police officer took notes as they outlined the threats. Theories had begun to spread that the Caller might have somehow gained entry to phones by targeting accounts on Myspace, which had somewhere around 50 million users and was near its peak in 2007. Spooked, Taylor deleted her account.

It wasn’t until after the meeting that Taylor and Andrea discovered that although both of their phones were off, Taylor’s had somehow turned on and texted Andrea during the meeting. According to a Gig Harbor police report about the incident compiled by astonished officers, the mysterious suspect “was able to overhear [Taylor’s] conversation with the officer and [later] threatened her for reporting the harassment.”

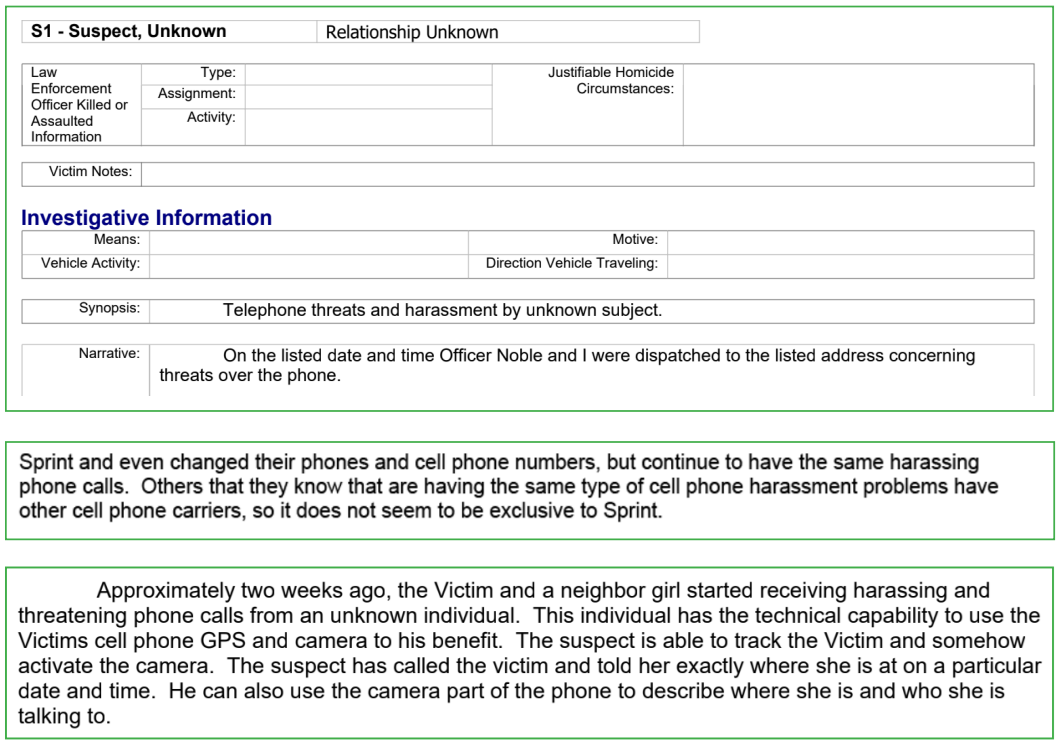

The Shaws bought new phones with different cell providers, but even then they didn’t shake the Caller. “The suspect is able to track the Victim and somehow activate the camera,” noted the police report. “The suspect has called the victim and told her exactly where she is at on a particular date and time. He can also use the camera part of the phone to describe where she is and who she is talking to.”

As with the other victims, the harassment became more frightening. Spencer, Taylor’s brother, received a death threat. The victims hardly seemed wise targets to try to intimidate. Spencer was on his high school football team, and the dad, Darren Shaw, was the Gig Harbor High coach. Courtney’s father, Tim Newhouse, had been a baseball star at Washington State, receiving the Pac-10 Player of the Year in 1989. Yet they all felt themselves at the mercy of the Caller.

Major Sayer on a tour of duty.

The same applied to Major Richard “Dick” Sayer, a 26-year veteran of the Air Force. He served in Iraq and would receive the 2009 Grover Loening Award as part of the 728th Airlift Squadron, given to the best Air Force Reserve flying squadron. Sayer was stationed at McChord Air Force Base near Tacoma when he received a cryptic message followed by death threats. Considering his sensitive military position, he contacted the Tacoma Police.

In early March, Taylor received a message in which the distorted voice of the Caller warned that he was going to kill Taylor and her boyfriend that week at their high school during their first period Spanish class. Could the Caller have been one of the victims’ ex-boyfriends, or someone who considered himself an outcast from their circles, or a close friend who felt jealous in some way, or even a disgruntled authority figure from the school? Officers who heard the Caller agreed it seemed to be a man who was disguising his voice through distortion. Lieutenant William Colberg of the Gig Harbor Police Department listened to Taylor’s recording and asked her who it might be. She said she had no clue.

IN EARLY MARCH 2007, the scope of the problem came into sharper focus. What started as disparate incidents in Pierce County, Washington, at several high schools seemed to be part of an interconnected web of threats. Three families—the Newhouses, the Sayers, and the Shaws—seemed to be at the center, but friends and acquaintances in their cell phone contacts were affected, as if the harassment were a malignant virus that spread from phone to phone.

Earlier that year, Steve Jobs had unveiled the first Apple iPhone, telling a San Francisco audience that “today, Apple is going to reinvent the phone.” Jobs’s prototypical phone wouldn’t ship to consumers until late June. A study by Comscore released in December 2007 revealed that only six percent of users had smartphones—up from only three percent the previous year and compared with 85% today. Most cell phone users in 2007 had flip phones. However simple in the eyes of today’s users, they were still hand-held computers and were shaking up culture. Mobile carriers’ slogans reflected the promise of a better quality of life through these devices. “Join In,” urged Verizon in 2002, while “Get More from Life” was T-Mobile’s 2005 message and “Yes you can” was Sprint’s in 2006.

In addition to the new hardware, modes of communication like texting brought new customs. The first recorded text was a developer who sent “Merry Christmas.” The start of 2007 was nine months removed from the formation of Twttr, later Twitter, as a SMS (Short Message Service) text platform that was transforming social interaction with a format both interpersonal and disconnected.

Law enforcement struggled to keep up with the burgeoning technology. Cynthia Fraser, a technology safety specialist with the National Network to End Domestic Violence, had observed the varied and surprising ways that cell phones factored into stalking cases. In 2006, she noted that exes could be tethered to each other by their cell phone plans. That same year, a Seattle man named Robert Peak had stalked and harassed his estranged wife by tracking where she was through phone GPS and intercepting her emails and texts.

The law enforcement community had other examples of supposedly secure systems being seriously compromised. In 2005, a 21-year-old man in California was arrested and charged with hacking into T-Mobile’s network in order to try to sell social security numbers and other private information. He managed to hack into a Secret Service agent’s email account. In 2006, a 23-year-old hacker in Spokane, Washington, also named Robert was charged by authorities with wire fraud though he would remain out on bail until the fall of 2007. The scheme by Robert and an accomplice in Venezuela involved intercepting a company’s customer service calls and rerouting them in order to obtain personal information and codes. Years before the fraud charges, Robert was caught after sending 40,000 text messages to customers of Cricket Communication. “One of the reasons I was so addicted to computers was I found I didn’t need the real world,” he explained. “I had the online world, where people loved me.”

The intricate, confusing Washington State Caller case now involved police departments from Tacoma, Gig Harbor, Fircrest and University Place, along with the Pierce County Sheriff’s office. “One of our tech guys who should be looking for child porn has spent 50 hours doing nothing but this,” said spokesman Ed Troyer. “This is nothing any of us have ever seen before.” The incidents were insidious and technologically cutting edge, arguably unprecedented for the way the Caller gained complete control over the dialing, texting, camera and recording functions of dozens of phones while leaving no traces behind of how it was done. Investigators uncovered the fact that one victim, whose identity they kept under wraps because she was a minor, had previously been harassed by a local construction worker who had been a youth minister before he was fired for alleged inappropriate conduct. When reported by the harassment victim during his time working construction, he sent her a flurry of text messages and called her cell phone late at night. It seemed a stretch, with no sign of hacking or sophisticated use of technology, but the police put in requests to find out if he had any connection to any of the cell phone companies.

Cross-department meetings became a regular occurrence, and the longer the harassment continued, the more that local authorities appeared powerless to stop it. “We’re almost dumbfounded,” Fircrest Police Chief John Cheesman said, echoing Troyer. “We’ve never seen anything like this.”

2007 WAS THE 50TH anniversary of Curtis High School’s opening. One of its most famous alumni Gary Larson was said to have drafted early versions of The Far Side during science classes, with one iconic recurring character looking exactly like a longtime biology teacher at the school. Larson’s sardonic, contrarian cartoons reflected the surreal feeling that descended on the community, with devices meant to make them safer and happier suddenly placing them in danger instead.

Principal David Hammond was an affable leader who had risen the ranks at Curtis High after several years as a classroom teacher at other local schools. He was as stumped as the local police by the shadowy terror cast by the Caller.

On March 7, Courtney Newhouse, frantic, rushed to the main office after lunch to talk to Hammond, who was joined by University Place Deputy Doug Shook, the campus police officer. When she left her second period class, Courtney noticed a man in his early twenties waiting outside of her classroom whom she had never seen before. She was certain that he wasn’t a teacher or staff member. He was unshaven and wore jeans and a black hooded sweatshirt pulled down over his head to his eyes.

The man followed her to her third period class and was there at the end of the period, following her to fourth period. He did the same after that class and followed her into the cafeteria where he “sat alone at a table near hers.” She said that while near her in the hallway, he made “heavy breathing and scary raspy grunting noises,” the same as those left on the many voicemails.

The Newhouses also claimed that someone came to their home at night—throwing eggs, screaming, hitting the outside walls. Strange cars would park at the curb. The voicemails continued:

I’m warning you. Don’t send them to school. If you do, say goodbye.

I know where you are. I know where you live. I’m going to kill you.

PIERCE COUNTY Sheriff’s Officer Gregory Dawson, 48, began working the case. A former Army pilot, Dawson had been in law enforcement for 20 years and began working on technology cases after training in computer forensics. In hunting down the Caller, Dawson focused on the “possibility that there was a compromised military serviceman,” centering the brazen threats against Major Dick Sayer in his reports to supervisors.

The case took on a heightened urgency. Dawson consulted Jeffrey Schwab, a Special Agent from the U.S. Customs Enforcement office in Seattle, who traveled to meet with Dawson and other investigators. Special Agent Schwab stressed the “difficulties” of the cell phone exploits that were described by victims. In his report of the meeting, Dawson explained that “it seemed more like someone had possibly gotten physical control of one or more phones and possibly set some setting to allow it to be manipulated in some way to fit a ‘social engineering’ scenario of some type.” In cybertechnology, social engineering refers to the infiltration of a computer system. Special Agent Schwab had never seen such “far reaching exploits” of other phones in previous investigations.

Investigation documents obtained by Truly*Horror.

Police continued looking into the disgraced youth minister (now a construction worker) though no evidence emerged of any special access to the cell companies or of any special expertise. Nor were there any jilted suitors or estranged friends of the victims who would have possessed the characteristics or skills that the Caller needed.

Dawson agreed with Schwab that it seemed that the Caller must have had direct, physical access to one of the phones. This hypothesis was shared by Tacoma Police Detective John Bair, whose work on the case led to a pivotal turn of events.

Detective Bair had a diverse career. He served in the Army during the late 1980s as an artillery repairman stationed at Fort Bliss in Texas before joining the El Paso Police Department. Relocating to Washington State in 1992, he joined Tacoma’s police force as a detective. Bair’s work in the auto-theft task force was notable, but his ultimate expertise was in mobile forensics. A deft, methodical investigator, Bair was tapped to extract evidence from mobile devices during violent crime cases. Departments across the Pacific Northwest sought his assistance on complex cases, and he taught at mobile forensics labs for U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and the Secret Service.

On March 8, 2007, Bair collected 11 affected phones, including phones that were no longer in use. While Bair conducted forensic examinations of the phones, Dawson continued his own work. He followed up with Deputy Shook, the officer stationed at Curtis High School. Shook and Principal Hammond reviewed the tapes that showed Courtney Newhouse the day she made her report at the high school but could not pinpoint someone following her, “nor did anyone else report this ‘stranger.’”

School security cameras in the county were not without controversy. Only days before the first activity of the Caller, a recently upgraded security camera system at Gig Harbor High (Taylor and Spencer Shaw’s school) caught two girls kissing. The dean of students proceeded to release the footage to the girls’ parents, leading to one of the girls transferring to another school. On Myspace, an unidentified poster wrote “I could make the deans life verrrryyy difficult for a few days if you want me to.” The dean was soon dismissed.

The area schools’ cameras had been intended to catch disruptions and rule breakers, and there had been plenty that spring from every direction. A student at Curtis High brought a BB gun and air gun to school and was taken into custody by police, while the 15-year-old son of a state trooper was arrested after stealing three of his father’s handguns and bringing them to campus. A middle schooler made threatening comments to classmates. The Tacoma police increased the presence of officers at schools across the area.

Meanwhile, Bair’s examination of phones from the Caller’s victims yielded new evidence with unclear significance: one victim had used the code *67 as “a prefix to some outgoing calls in her phone…. This is a known code that restricts the number of her phone being displayed on the caller identification feature of the receiving phone.” Another Pierce County sheriff’s deputy questioned the victim, and she denied doing so.

For his part, Deputy Dawson ultimately wavered. He theorized that some of the features of the reported manipulation resembled phone cloning, but observed that it was “a more difficult technical process” to accomplish with newer phones. Dawson affirmed that only someone with “specific expertise” could generate anything like the Caller’s exploits. In fact, he surmised it would “probably [be] an expert from the manufacturer,” a description which did not fit anyone they could identify.

Police did look into the fact that one of the teenage victims being harassed was involved in testifying against an adult male in the community for sexually assaulting her. There was an investigation into whether the accused assault perpetrator or one of his family members could have worked for one of the cellular phone companies, but the outcome of that line of inquiry remains murky.

Dawson said: “I can’t escape the belief that there is someone involved in this that hasn’t completely divulged what they may know about this series of incidents.”

The Caller, meanwhile, continued harassing Courtney at school.

We know you’re in your child psych class. Don’t think we can’t see you.

Get the fuck out. We will kill people at Curtis when you least expect. All your stupid fucking friends.

Although there were another two weeks left in the school year, a traumatized Courtney was granted an early release. They could all feel safer with her parents’ new alarm system—that is, until the Caller made sure they knew he had their code. “I can’t even be by myself at home,” Courtney lamented. “I don’t feel safe at all.” Courtney’s younger siblings refused to sleep in their own beds, insisting on sleeping with Heather and Tim. “It’s hard as a mom to see your kids be scared like that,” Heather said.

With the school security cameras inconclusive, those who doubted that the Caller had a physical counterpart were jolted by what David and Barbara Nasberg of Tacoma reported. They publicly voiced their support for the victims of the Caller. Then they, too, began receiving electronic harassment. It started with obscene messages, then they discovered their daughter’s bedroom window open one night. The screen was “knocked out,” and the nightstand was “kicked over.”

DETECTIVE BAIR stressed that the key to the investigation could be securing call detail records, which had to come from the cell phone provider and could not be manipulated by an end user or a purported victim. On March 14, Deputy Dawson submitted a search warrant to Sprint for phone records.

He was passed around to different departments, all of whom had the same basic answer: “We don’t do that.” Dawson, befuddled, concluded: “I was going to have to attempt to solve this case within my own resources because Sprint was wasting time.” When Sprint finally provided the police with the call detail records, they provided little new information. An investigator from Sprint observed that, of all the possible manipulations of cell phones, “the one phenomenon he had never heard of was the remote turning on of the phones.”

Some of the families involved decided that if the police weren’t making progress, they needed the help of the public to solve the mystery. Besides, it was only a matter of time until the incidents were talked about beyond their communities. The families turned over several voicemails to the News Tribune, a Tacoma newspaper. A color photo in the paper showed multiple phones—some in ziploc bags, others with batteries removed—strewn across a kitchen table.

Darci Sayer lamented that the police “kind of pushed us aside I think a little bit…. [W]e had to come to the media for help to try to solve this. It’s been traumatizing and terrorizing for all of our family, our extended family, my children. It’s unbelievable.” They were featured on morning news shows and even in a segment of the Tyra Banks show.

Speaking to the media created some friction with investigators, whose irritation may have pushed them to lean into one of the theories at play: Courtney, the first victim, had to be behind it all. The call records had confirmed that many calls and messages originated from Courtney’s phone. Courtney and her family balked at this, pointing out that they were the ones to come to the police in the first place with the information of her phone being “electronically hijacked.” Courtney, with notable poise for a teenager, was adamant. “Why would I do that to people I care about? Why would I harass my own family?” She and her family tried to think whether any of her ex-boyfriends would target her that way, or if there was someone who wanted to punish her for her popularity at school.

Heather and Courtney (Source: News Tribune)

Andrea Shaw was convinced that whoever or whatever was behind the calls had started with Courtney’s phone and somehow infected it, reaching into her contacts and then spreading to other families’ contact lists.

The Pierce County Sheriff’s Office demurred. Spokesman Ed Troyer, who had expressed frustration with the resources being absorbed by the case, said: “At this point, we aren’t saying it’s someone inside the family, but it’s someone that is close enough to them to know this much about them. It seems like it’s someone who is tied into the group, a family member, a friend or an enemy. I hope it isn’t coming from within the family because it would be a waste of everyone’s time.” A few days later, he remarked: “Everyone, even within the cell phone industry, is telling us it can’t be done.”

Soon Heather told news outlets that Courtney “was too upset to speak” about the case. The media requests were overwhelming, and the attempt to get help from the public seemed to make things worse.

Most disturbing, the attention had not stopped the Caller. Courtney was babysitting two children and had her phone with her. She and other family members had taken to covering the camera, believing that the Caller could view them through the lens or record their actions.

Courtney’s phone rang, and someone said they knew where she was. The Caller then called one of the young girls’ phones, frightening her.

WITH THE MEDIA attention, the case became irresistible fodder for online sleuths—a venn diagram of burgeoning cell phone hacking, the dawn of smartphones and privacy fears. Blog posts with titles like “Cell hack geek stalks pretty blonde shocker” launched debates in the comments, with one user, Edwin, noting that the fact that most victims used flip phones and not smartphones actually made hacking from a distance less plausible. Most commenters believed the more outlandish exploits were well out of the reach of your average cell phone user, with one, Steve Roper—a former hacker himself—conjecturing, “it’s entirely possible some geeks at her school have ordered some of this stuff in and had an opportunity to doctor her phone. It beggars [sic] the question, what else have they done? They could bug her house (I’ve seen a device that aims a laser at someone’s window and can hear a conversation in a room a mile away), which would account for her conversations being heard while the phone was turned off. Such a crew could also have placed hidden cameras and remote mikes [sic] around the neighborhood—given the ready availability of such technology these days I would not be at all surprised.”

One commenter posted a link to Courtney’s MySpace page, which not only nodded to the ubiquity of the social media but also raised the concern that browsing the site on her phone might have invited some kind of virus or other intrusion.

Discussions flourished on MetaFilter, where the first commenter, mrbill, bought into the Courtney conspiracy theory: “[M]y money is on all of this being caused by the teenaged daughter.” Another was less convinced. “This seems like a lot of effort to go through to scare people. I guess the easy solution to the night banging is to have a cop stationed nearby, but I guess they’d probably figure that one out before the phone even got hung up!” posted invitapriore. “Probably harmless, but what an involved sadist….” Another user, puke & cry, theorized Courtney was framed: “I just figured it was some poor bastard schoolmate of the girl that has some kind of inside track at a cell phone company.” This fit the notion of an ex-boyfriend or an aggrieved family member of the man who stood accused of sexual assault.

Commenters at MetaChat had a nefarious theory: the incidents were tied to McChord Air Force Base, where a Special Tactics Squadron with “some nice radio toys” was stationed. Commenter trondant conjectured that some kid had “gotten his hands on some of Mom or Dad’s work toys, and is having a grand old time of it, raising Merry Hell and fucking with people he knows and very much dislikes.” Another user, cmonkey, had a warning: “‘RESTRICTED’ in WA is really going to regret this stupid shit when he gets caught, I think.”

Even internet denizens ready to tear people apart could not quite account for how it might have been a hoax, as some believed. Due to the many victims involved, it would likely require a hoax of significant proportions. At MetaFilter, user Avenger found the key moment to be the babysitting incident when an 11-year-old girl whom Courtney was babysitting became the latest victim: “[B] eing able to somehow hack into the phone of a random 11 year old girl who just happens to be standing next to the victim? Thats [sic] some Matrix shit right there. Impossible Matrix shit, to be exact.” Avenger concluded: “I mean, really, what are the police supposed to do when presented with presumably impossible events?”

A few hours later, on the same forum, parallax7d offered an enticing comment: “[Hoax] seems possible to me, but the amount of expertise to pull this off seems amazing. Perhaps someone with intelligence training.”

It seemed hardly conceivable the Caller was one person, or even multiple people, but rather it felt like some kind of semi-sentient presence in itself, a manifestation of the toxic side of the technology so often promoted as connecting society even as it threatened to tear it apart.

Given what seemed to be an impossible situation, even improbable angles had to be entertained for those trying to fit puzzle pieces together. Reddit user Lusonectes commented, “this sounds like a modern poltergeist experience. It is temporary and intensive, begins and ends without a clear reason, has an escalation to it, is centered around a teenaged girl.” In fact, an unconventional sector of study quietly developed for more than 40 years into so-called electronic poltergeists or electronic voice phenomena. Distorted and disassociated human voices combined with technological anomalies, as in a 1927 case in Whately, Massachusetts, in which a ghostly voice purportedly appeared on phone lines praying the Rosary while also screeching “blood curdling cries of death, hunger and pain,” as reported by the Transcript-Telegram newspaper. A local school teacher collapsed “as a result of the weird voice,” and telephone operators refused to work.

In the late 1970s, a California industrial plant reported being wracked by electronic disturbances. The incidents appeared to focus on a female employee named Gladys, whose mere presence at the facility allegedly caused “high-pitched electronic sounds” that shrieked through the telephone and paging systems. Telephone buttons would alight randomly. Paging speakers at other ends of the plant would boom sounds then stop. Gladys confirmed to one investigator that her car radio, as well as her phone and television in her apartment, often acted in similarly strange ways in relation to her emotional state.

David Nasberg, the Tacoma resident who found his daughter’s bedroom window screen knocked out after receiving threats, unwittingly echoed the studies of electronic poltergeists when he concluded “It’s almost like it’s a damned ghost.”

BACK IN FIRCREST, Heather Newhouse was at her wit’s end. There was no escaping the harassment. She recalled how the Caller phoned once when they were out on a hike, with no one in sight. The stalker described what they were wearing, and their exact location.

Get out of the woods because we’re going to kill you.

“It feels as though we’re living in a scary movie,” Heather said as they, too, seemed to be on the run from an invisible predator. “They know they’re terrorizing us and they love it. They thrive on it. I just don’t see how our lives will ever be the same.”

The investigation became far less transparent after the victims’ short-lived media participation. Detective Bair told Truly*Horror that although they caution victims about bringing their story to the media, the police ultimately cannot stop them from doing so. “I don’t begrudge them for doing that,” he said. His concern, shared with other investigators, was that such publicity would muddle the case.

Around that time, Officer David Seele of the Fircrest Police Department told Officer Fred Douglas of the Gig Harbor Police Department that “all of the local police reports were turned over to the FBI, and they were now looking into the situation.” Douglas tersely concluded a June report: “Case is suspended pending new information developed by the FBI or any other related agencies.”

From available evidence, the final calls and messages from the Caller came around that time the FBI became involved. Without definitive closure, it was not hard to understand victims’ fears that the Caller would emerge again.

Bair told Truly*Horror that he did not work with the FBI on the case. In fact, he was surprised to learn from Truly*Horror of the FBI’s involvement, and conjectured that it might have arisen due to the recording and surveillance of law enforcement. During the course of the case, recordings of multiple police officers were reproduced on calls, and apparently one police officer’s own phone was exploited. By the investigators’ own previous logic, once law enforcement phones had been compromised, a suspect could come from inside law enforcement. The FBI, meanwhile, has denied our repeated requests for more information, citing bureaucratic protocol.

Darci Sayer, one of the victims, ultimately had her own theories. She believed the Caller was actually a group of people, possibly using sophisticated software, and pointed to the fact that multiple people would be called at once.

The Caller and any potential accomplices remain unidentified.

WITHOUT RESOLUTION, those who went through six months of hell starting in the winter of 2007 admitted that fears persisted, as did the stress from some observers continuing to blame some or all of the victims. Some victims and witnesses who were contacted for this story quickly changed their social media security preferences to be harder to find. This could be interpreted as a sign of guilt, or personal exhaustion, or fear of the Caller or even of the investigators.

Taylor Shaw received her master’s degree in criminal justice from Seattle University in 2015. Her father Darren ended up switching from coaching football at Gig Harbor High School to coaching at Curtis High, and Spencer Shaw coaches alongside him.

Heather Newhouse, now a realtor, tried to find silver linings to the incidents. “It empowered me to be stronger for our family, and we’re tighter because of it.”

At one point, Courtney admitted that she had been “accused by the FBI” of hoaxing the calls, though they may well have been employing tactics to see if she or anyone else would volunteer some kind of admission to bring closure to an unsolved case. For those suspicious of Courtney, no one ever articulated a plausible explanation for how she could have had the technological prowess that even the investigators did not possess to manipulate phones as witnessed by many, including police officers. Here is one of the conundrums of the case: if it were a hoax, who on earth could have pulled it off in 2007? Courtney and the other victims remained consistent in denying any involvement. She currently works as an ER nurse in Tacoma.

After 26 years as a detective, John Bair established a digital forensics program at the University of Washington and now serves as senior consultant and testifying expert at Lighthouse Global in Seattle. Bair admits the Caller case remains a conundrum. Whoever was behind it used “elaborate technology,” the likes of which he has never seen again.

Pierce County Sheriff’s Deputy Gregory Dawson died in 2010 after a two-year battle with brain cancer. His comment on the case as possible “social engineering” referred to cybercrime techniques but evokes the broader meaning of the phrase: an attempt to influence behaviors of a sector of society. The far-reaching nature of the incidents— spanning a county, multiple high schools, and victims ranging in age from 16 to 76— suggests something more expansive than conventional cases of stalking, which often have one or few victims. The implication by Dawson seems to be that the Caller used cutting-edge technology to initiate a kind of experiment upon the communities, a game designed by a person with a God-complex to observe how fear and blame would be distributed. With that in mind, no wonder the disgraced minister was an appealing suspect, someone possibly out to prove a moral code superior to others. Was there a warning embedded in it all that if we didn’t properly control our phones, our phones would come to control us?

Some technological anomalies are never explained. In fact, only months before the Caller’s reign, the Seattle-Tacoma International Airport control tower went completely silent for 25 minutes, without any contact with air traffic. This potentially life-or-death technological blip was a mystery

Robert, the prolific hacker who scanned telecom traffic, opened up to a technology reporter about the scope of his technique before he went to prison in late 2007. “Even if it was not a telecom, they might be connected to a telecom and then you could move through that connection to the telecom…. I know I scanned a lot of people. Schools. People. Companies. Anybody. I probably hit millions of normal [users], too.” After serving two years at the Federal Correctional Institution in Oregon, he began work in cybersecurity. “When they say ‘Where’s your degree?’ you just show them your prison record.” There were up to 40 alleged victims of the Caller. At least one victim ended up arrested in later years on seemingly unrelated charges of auto theft and obstruction of justice.

In the weeks after email inquiries were sent to participants and witnesses and files were requested to report this story, a series of Facebook profiles were put up, all called Restricted Calls, all with zero friends and followers and random photos of a variety of happy families, with several listed as being located in Tacoma, Washington.

One legacy of the Pierce County Caller case was the coordination among multiple police departments and federal agencies. Federal officials with expertise in espionage concluded that whoever was behind the Pierce County harassment had Homeland Security-level expertise, arguably ruling out everyone authorities managed to track down. In one of their meetings in which investigators compared notes, a federal official reminded the group before starting to “close the door, turn off our phones.”