A GROUP OF TEEN OUTCASTS FROM A TOUGH SCHOOL INVESTIGATE AN ABANDONED MANSION. A SKEPTICAL EDITOR FROM TRULY*ADVENTUROUS IS EMBEDDED WITH THEM AS THEY UNCOVER THE HOUSE’S SECRETS, AND REVEAL THEIR OWN.

Caroline’s hair drapes from its center part and flows over her shoulders where it becomes indistinguishable from her black overcoat, especially in the darkness.

When she speaks her breath freezes, floats upward, dissipates.

Standing in the parlor of an abandoned one hundred and eighty-year-old house, the visual is unsettling.

“I think there’s a place that we go to, but I don’t… I don’t think it’s…”

That’s her reply when I ask if she believes in an afterlife. She trails off.

It seems strange that Caroline, the president of her high school’s paranormal club, would have no clearer ideas about the beyond. But frankly, it seems strange that she is president. Though not shy exactly, she’s certainly the most reserved member of the group. Just the same, she does seem to approach the evening’s outing more seriously than the others. And the uncertainty she has about what exists past death proves a common thread among all of the teens that have come to explore the house tonight. They share an unshakable faith and reverence for the almighty something.

“When you have supernatural experiences,” I ask, “do you think that that’s comforting or upsetting? When you think about these beings that are still present even though they’ve died?”

“I feel fine with it, but… sometimes it scares me.”

She describes her first experience. She was Hula hooping in the yard of her grandmother’s house with her brother when she saw an old woman standing on the porch. A withered face obscured by the shade against the wash of sunlight stared down at her. After turning to tell her brother, she looked back and the woman was gone.

That night, after returning to her own home, Caroline was going to sleep when she looked over and saw the same woman sitting in a chair in the corner.

When she tells the story, she does so with a sincerity and intelligence that makes it hard to dismiss. She plays flute in the school band, had the lead in the school musical before they had to cancel it for lack of support, and plans to go to college for music therapy. Her default expression is a smile, though it seems tired. Unsurprising since on top of school and the litany of extra curriculars, she works at a bookstore.

Whatever a typical member of a high school paranormal club might be, Caroline probably isn’t it.

Which isn’t to say I have a handle on a typical member. Though I’d searched for every one I could find online, I wound up with a list of fewer than ten high school paranormal clubs in the whole country.

One of the typical results was an old web page listing a phone number that no longer worked. When I called the high school itself, no one I spoke to had ever heard of the club, and I was told that the teacher whose name had been listed hadn’t worked there in years.

At another school, the receptionist said the club had folded and again, the sponsor no longer worked there.

In most cases where the club did still seem to exist, my calls and emails were met with either a firm lack of interest in discussing it with me, or silence, or even fear.

One sponsor sent me an encrypted email set to be deleted automatically after twenty-four hours, and which blocked me from highlighting or copying the text. It said, more or less, that his club had only just been reinstated after being closed as the result of a lawsuit from religious parents, and he didn’t think he could afford any attention.

In the end, this was the only one that had been open to talking, much less having me visit.

Caroline says there was a boy in the club once who claimed to be an empath. She pauses and looks at me searchingly.

“Do you believe that people have empath abilities? Can see or hear…?”

Earlier that day, in the middle of third period, their high school’s hallways were mostly deserted apart from a pair of contracted security guards called in to escort a rowdy student off campus. Dave Roberts, the club’s sponsor, later said three particularly bad fights had broken out that week, one of them spilling over into the parking lot of the McDonald’s down the street.

When he isn’t chaperoning the paranormal club’s outings, or running his own investigations with his side business, the Capital Area Paranormal Society, Dave teaches social studies. I wait outside his classroom and read neon post-it notes students have tacked to the wall in a long row. They fill the hallway with an array of the ambitions of students in a poor community. “I will stay in school all year… Because I Said I Would,” “I will apply for a work permit so I can help my parents financially and I will save up for a car for my sister… Because I Said I Would,” “I’ll be the first in my family to go to college… Because I Said I Would.”

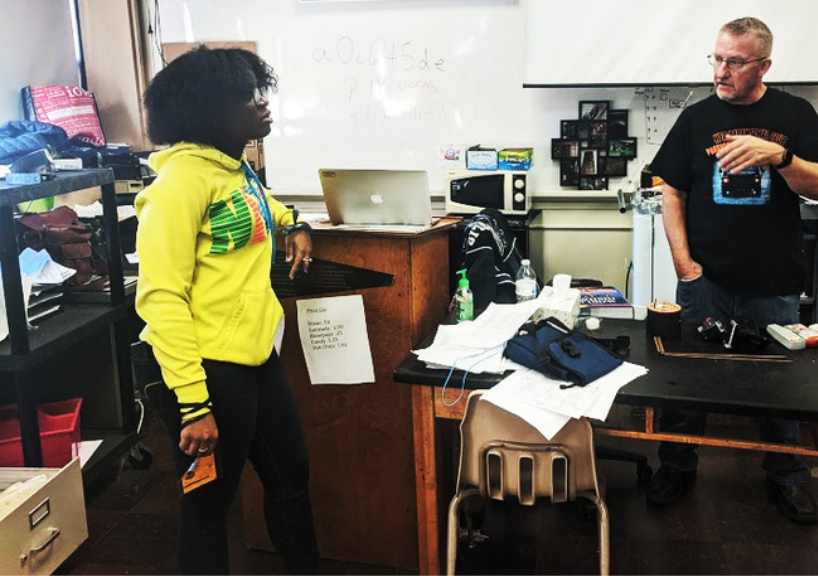

Dave pokes his head out from the classroom and smiles at me, motions me in. He’s only a couple of years from retirement, but has the buoyancy of a much younger man. Half the things he says seem like a joke he’s letting you in on and you almost expect a nudge in the ribs to accompany each one.

As his students work on a lesson on school-provided MacBooks, he cracks open a small case and begins laying out his paranormal detection equipment.

There is a “Mel Meter” that detects ElectroMagnetic Fields and temperature, then displays the result on a small digital screen. It was invented by a man who designed the device to communicate with his daughter, Mel, after her passing. I wonder for the first time whether anyone develops an interest in the paranormal for reasons other than an inability to move on. Beside the Mel Meter on his desk, Dave places two additional ElectroMagnetic Field detectors, one which uses a needle to display the level, another with a series of LEDs, going from green to red.

Next, there is an Instrumental Trans-communication box, which scans the air for specific frequencies and will, under certain stimulation, return a random word from its internal dictionary that on occasion has eerie relevance. An infrared floodlight allows for better photographs. There are others, with so many subtle variations on what they do it becomes difficult to keep them straight. Some cost the better part of a thousand dollars, all of which has come out of Dave’s pocket. He keeps a shelf in the classroom stocked with Cheetos and Gatorade which he sells to students to support the club. It doesn’t go far in offsetting the costs.

As the electronic bell chimes over the loudspeaker, students return their laptops to Dave’s desk, a couple handing over fistfuls of change to take some of the snacks or drinks. Dave stops one of the students, an African-American kid with a cowed smile that looks like it belongs on someone half as tall.

“This is the principal’s son,” he tells me. “The principal loves the paranormal club. Huge supporter.”

“Principal’s your dad, huh? What do you call him when you see him in the hallway?” I ask. He pauses a second.

“Um. Dad?”

“Yeah, I guess that makes sense…” I mutter.

Shortly after the room’s emptied out, a girl from the school newspaper comes in to snap a picture. She and a couple of other students are working on their own write-up on the club. Bouncy black ringlets explode from her head, framing thick glasses and a dubious grin. She wears a lemon hoodie and tight black jeans. Dave insists I get into the picture, which she snaps on her phone.

“Why don’t you come with us tonight?” Dave asks her.

“No way,” she says, “I’m not messing with that stuff. I don’t think my mom would let me anyway.”

The conversation segues off to the school’s home ec room, where the girl had seen the door slam shut, things fall inexplicably from the wall. Dave’s aware, it’s common knowledge throughout the school. The conversation makes her seem just as intrigued as she is frightened, but as we walk into the hallway, she continues to refuse Dave’s invitation.

She says her mom’s superstitious. Believes things like that can attach to you somehow. Follow you home.

The Virgil Hickox House, built in 1839, stands over a broad red brick avenue ending, only a few blocks west, at the Illinois State Capitol. Its ground floor is partially submerged, with steps leading down into a Cajun seafood restaurant, the facade of which takes up half the width of the building, the other part being a porch that rises to the house’s main entrance.

It started off as the home of its enduring namesake, Virgil Hickox, a wealthy businessman remembered as a friend both of Abraham Lincoln and his rival Stephen Douglas, but really much closer to the latter. After his death in 1880, Hickox’s home spent over two decades as a club for well-heeled gentlemen in the community, then, a much shorter time as a funeral parlor. Other businesses had shorter stints until a popular local tavern set up shop for the majority of the 20th century.

When I had learned earlier that the house had once been a funeral parlor, I felt excited to find some sort of basis for its haunted reputation, but Dave disagreed. While he said he had once heard a banging then a dragging from upstairs, that sounded, he thought, like a coffin being pulled across the floor, he didn’t imagine a funeral parlor as being the place a person would linger after death. Seemed more likely to him people might return to it if they had been members of the men’s club, staying in the place they had been happiest. Which made sense. Why would the dead be any less likely to chase happiness than the living?

Twilight comes as a hard blue sheen, replacing the day’s gray. Patches of packed snow mottle the sidewalks, remnants of a recent storm.

I take a couple pictures of the building’s exterior before my phone suddenly freezes up. It crashes and won’t restart. I’m forced to do a factory reset and pray it doesn’t happen again. I can’t afford to not get any pictures.

With time to kill waiting for Dave and the students, I go into the restaurant and take a seat at the bar. Dave had warned me that the restaurant’s proprietor, who leased the space from the building’s owner, resented the paranormal investigations and any talk of hauntings.

“He said he was going to get a priest out to have it blessed,” Dave told me earlier. “And that he doesn’t believe in any of that stuff. That he’s a Christian.”

“Why have it blessed if he doesn’t believe in it?” I asked.

Dave laughed.

“I hadn’t thought of that.”

Sucking up a plate of half-frozen oysters, I make tentative conversation with the waitress.

One night, the story goes, one of the wait staff had been closing up when she felt someone tug her ear. Spinning around, she found no one else in the room.

As I think about the story, I look to the other side of the restaurant where a mom sits across from her young son, sharing a basket of fried clams. I haven’t been away from home twenty-four hours yet, but I feel myself missing my own sons with a surprising intensity. The feeling seems like a misplaced unease only now coming on at the prospect of going through the house. I’d mentioned the assignment to a friend before leaving. He asked if I’d really go through with it and I scoffed.

“Of course.”

“I’d probably chicken out,” he said.

It hadn’t occurred to me that anyone could be scared. I never believed in ghosts, which is objectively odd since I believe in an afterlife that is, for the majority of people, incomprehensibly horrific.

Around the time I finish the oysters and walk back outside, the sun has set and the temperature bottoms out. Dave arrives, along with his girlfriend, Jody.

As I follow them up the porch steps, he pats the pockets of his coat for the key, which the owner has given him for tours. He apologizes for the dozenth time about the state of the interior. The owner, he grouses, is a bit of a hoarder.

Sure enough, a large table on its side leaves only a skinny gap to squeeze through. Dressers, boxes, lamps, books twisted from damp climb the walls and create mazes through the high-ceilinged rooms. I push the door shut behind us and reflexively flip a light switch, but nothing happens. “Only the little room in the back has electricity,” Dave explains, and Jody and I contort ourselves through the piles, following him towards it.

The room, like all the others, contains stunning vestiges of its former glory. Behind the Casio keyboards and dot-matrix printers, gold embossed wallpaper fills the gaps between carved oak panels. A fireplace mantle holds up the detailed model of a three-masted schooner, and a kerosene lamp opaque from dust.

As Dave clears off a metal workbench to lay out the case full of equipment, a knock comes on the front door. Jody heads off to open it, but calls back that it’s locked.

Dave and I make our way over, as he insists that she’s wrong. There’s no latch, you have to use the key to lock or unlock it from either side, and I’d been the one to push it shut. But when Dave tries to budge it open, it turns out that it is indeed locked. He fishes the key back out of his pocket and works the lock free. The whole thing leaves me perplexed, but Dave seems too unsurprised to bother questioning it.

The next kid to arrive after Caroline has tufts of adolescent hair like shadows on his cheeks and upper lip. Twitchy eyes, headphones around his neck, and a bright orange paranormal club hoodie, the same that Dave is wearing.

If Caroline seemed somehow out of place, he has stepped straight out of central casting. I ask his name.

“Damian.”

Of course it is.

Like Caroline, he’s had personal encounters, and most that he describes seem to have taken place in his bedroom, “playing games or watching YouTube.” Though when he mentions gaming he sheepishly adds “I’m trying my best to cut back on them.”

“I was in my room. I’m not sure what time of day it was. Out of the corner of my right eye I saw a white mist come straight down … I was like, what the heck? What is that? I mentioned it to my mom and my dad. My mom said that was my grandpa … my grandpa passed away.”

As I’d done with Caroline, I asked Damian how he felt about it.

He answered that he liked the idea of the old man “looking down from somewhere and just … thinking how proud he is. I just had that weird feeling that he’s always, like, watching me or guiding me in the right direction. Somewhat …”

The group gathers in a semi-circle around the work table, Dave’s equipment laid out over it like a surgical tray in an operating room. He encourages everyone to grab one of the devices and head upstairs.

David Ridenour, the building’s owner, slinks in with a proud smile that suggests he considers himself the patron of the event. In spite of Dave’s repeated grousing over Ridenour’s hoarding, he’s quick to ask if he can buy one of the lamps that caught his eye. Ridenour hems and puts him off and Dave tries to get everyone upstairs.

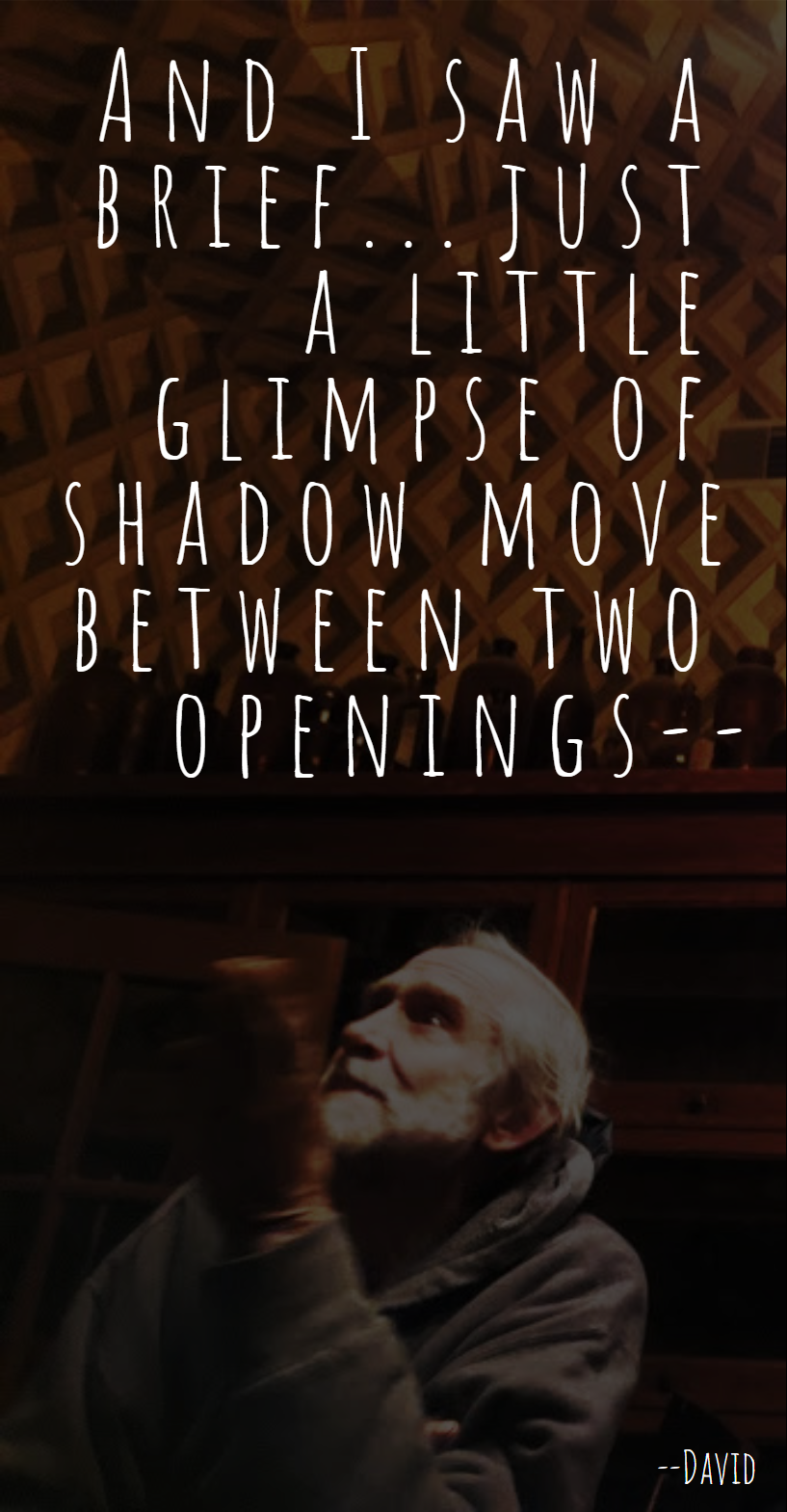

“Can I tell them all my paranormal anecdotes?” Ridenour asks, not even bothering to wait for a response before starting in. “Several years ago, I was sitting up on the staircase at the turn in the stairs and my painter was on the foyer on a ladder. And I saw a brief … just a little glimpse of shadow move between two openings — ”

Damian excitedly interrupts:

“I … I saw that … happen to me. I was sitting on the couch across from one doorway, I saw a shadow figure — ”

“Yeah, a shadow!” Ridenour concurs. They talk over each other a few moments before Damian yields the floor.

“It was just a fraction of a second,” Ridenour concludes, “and I said to my painter I’m not sure, but I think I might have just had my first paranormal experience and you know what he said? Oh really? I thought it was just me!”

Ridenour beams as the group laughs approvingly. The students follow up with their own animated recountings of experiences in the house as Dave once more tries to get everyone on task.

A student named Ian approaches me and introduces himself.

Like Damian, he speaks haltingly and his eyes dart down anytime you catch them. I try asking him something but he beats me to it.

“You’re from New York? What’s that like? How long are you in Illinois for?”

“Just today.”

“You have to go to Alton. Most haunted town in Illinois, I’ve even got the shirt.”

He pulls his jacket open to reveal a t-shirt with a cartoon of a creepy Victorian mansion under the words Alton’s Most Haunted McPike Mansion.

“How far away is it?”

Ian squints and cocks his head as he runs numbers in his head.

“About four hours. You got a favorite band?”

“Favorite band? I think it would probably be something really lame like Coldplay.”

“I’ve got several favorite bands.”

“I probably haven’t heard of them.”

He taps his phone screen to pull up an album cover and holds it over for me to see. “Greta Van Fleet?” I read.

“They’re a modern band but they do classic rock, which is why I love them so much. Have you ever been to any Civil War sites?”

The group has mostly gathered up their equipment and followed Dave toward the winding staircase that leads to the upper level. I start after them.

“I’ve been to Gettysburg,” I say.

“I’ve been to Gettysburg, Shiloh, Corinth, Pilot Knob…”

We congregate in an upstairs bedroom that still almost looks the part. A brass-framed bed is in the center, though chairs are piled on it, not unlike the lamps crowded onto a corner bureau. The walls, at least, are uncluttered, a wood rail dissecting them into wallpaper above — a print of pale intertwined fleurs-de-lis — and dark blue paint below. Paintings hang from the walls, of Christ, waves crashing on a rocky beach, a patch of trees exploding into neon orange in autumn.

The room, at the front of the house, catches the glare of a street lamp just bright enough to fill the room with long, stark shadows. The group is clustered on the near side of the bed, the only clear floor space.

In the cramped darkness it’s hard to make out everything that’s going on. There seem to be a few stragglers that came late. Students I didn’t talk to and whose names I didn’t catch. Others seem to be equally uncertain, keeping track of new arrivals from the sounds of their voices coming from other rooms.

“Ian?”

“Yeah.”

“Caroline?”

“I’m here.”

“I think Alice is in here.”

“Definitely Alice,” another confirmed.

A student named Jackson, who, like Caroline, looks somewhat out of place in the club — if you ignore the pentagram medallion dangling from his neck — holds the Instrumental Trans-communication box out in front of him and asks “Is there anyone in this room?”

To say that Jackson’s beard is impressive for a teenager is an understatement and he’s built like a linebacker under his baggy Class of 2020 hoodie. The whole room focuses in silence on the device in his hand. It gives an electronic croak, like a b-movie robot, and a word appears on its LED screen.

The tension being what it was, I jumped when a voice whispered in my ear: “So I was out in the section of the battlefield at Gettysburg, they call it the wheat field, taking pictures, then I get back to the hotel, skimming through pictures, and in the bushes next to the monument, it looks like a soldier — ”

“Wow, that’s crazy,” I say, trying to listen in to the group discussing Jackson’s findings.

“It said PAT, STOMACH, SOLO,” says Jackson.

“My name’s Pat,” I say. Jackson, who had yet to notice me, looked over with surprise.

“And he came solo,” adds Dave with a laugh.

An EMF detector is placed on the bed. It has an arch of tiny lights across the front, bulbs that go from green to red. It sits with only the first green bulb illuminating the face of the student bent over it.

“It says zero.”

A moment later every light flashes across to the extreme red bulb. There’s a collective gasp, then it drops back to green.

“Can you make the meter go red again?” someone asks.

“If you are in this room,” says Jackson, slow and forceful in addressing some unseen spirit, “would you like to speak into this device?” He holds the box out in front of him. Everyone is silent. The walls of the room flash red as the EMF detector flares up again. It’s startling and a few students shout. Ridenour excuses himself and leaves for the night.

I follow him down the stairs, peppering him with questions. He seems less interested in discussing the history of the house than sharing his personal philosophies, which include the observation that we are all “on a speck of dirt flying through space” and that he has managed to get through life “without benefit of any sort of god.”

After a while, the group breaks up, heading off with their various devices to different rooms. I find Jackson in an office, sitting in a swivel-chair behind a heavy oak desk, covered with cartons of matches, a toy tractor-trailer, wood-clamps, and an old-fashioned banker’s lamp with the green glass shade.

I stand in the doorway trying not to intrude. A low train whistle echoes from somewhere far off. The box makes its electronic garbling sound.

“REWARD,” reads Jackson. Then a long silence. Ian joins me and says the ghost of Stephen Douglas haunts the Old State House. They give tours. It occurs to me that Ian seems only to ramble in the absence of other conversation, that he is less obsessive than just terrified of silence or his own thoughts. I wonder what they must drift toward.

“JESUS. Do you like to pray to Jesus?” Jackson asks some unseen presence in a loud, slow voice. “SHOULD”, he reads softly, casting his eyes around as if he might find the source. “Should you see Jesus?” Another pause. “UNDER,” he reads.

“Maybe,” I suggest, despite not wanting to involve myself, but too curious to resist, “Jesus should be the reward, but… they’re stuck here?”

“FELON.” Jackson looks up to explain to me “sometimes it doesn’t have a lot of words in the dictionary so it combines things. Either it’s felon like felony, or fell on…”

“From a Christian perspective,” I venture, “maybe it’s like they should have seen Jesus as the reward, but they’re under sin, like a felon — ”

The box goes off again, and Jackson reads: “KISS.” He turns his head up and speaks loudly: “Do you want a kiss?”

“Maybe they had an affair or something. That was their great crime.”

“Would you like a kiss?” Jackson asks.

A few seconds pass before the box flashes the word “CORRECT”.

“Oh, you want to kiss Pat?” Jackson laughs.

In the adjoining room, a later addition to the house without any of the grand wallpaper or panelling, Damian sits at one end of an oversized couch. I walk in, disoriented in the dark, trying as much as anything else to track down the students I hadn’t had the chance to talk with yet. Damian holds a pair of divining rods out in front of him. Caroline stands opposite, holding another pair.

They are by far the least technological of any of the equipment, copper tubes with thick copper wires placed into them and bent into an L-shape like a toy gun. Holding the tubes allows the wires to turn freely from side to side. Dave demonstrated them earlier.

“They don’t work for me,” he said as he stood holding them motionless.

“Has anything happened so far tonight?” I ask Damien.

He says Alice had a turn with the divining rods earlier and had them spinning all over the place. I’m skeptical, but watch as he settles in with them.

Sitting stock still on the edge of the couch, the copper wires facing forward, he asks “where are you?”

Slowly they begin tilting to the left, gliding over until they slow to a stop. “Are you in here with us? Cross the rods for yes, don’t cross the rods for no.”

I notice Damian’s eyes tilt up toward Caroline’s. She meets them briefly but as quickly turns back to the rods. It’s hard to read, in the darkness especially, how the pair feel about each other, though in Caroline’s case it hardly seems to matter. She’s too focused on the unseen in the room to bother with anything else.

After a few tense seconds, the rod in his right hand remains still as the left drifts back to the right, sliding over the top of the other. Then the other moves as well until, crossing, they each touch his arms. Damian looks up, smiling.

Throughout it all, Caroline seems detached, watching her own divining rods twist one direction, then another, with a constant, easy speed. She stares fixedly at them, never looking up.

Damian eventually sets the divining rods aside and picks up a spirit box, a small speaker connected to a radio tuner that sweeps through frequencies and pauses and progresses in response to electromagnetic detection.

“Be careful,” says Caroline quietly, not looking up. “It’s always loud.”

A few seconds later, an explosion of static shocks the room. Damian jumps and wrestles with the volume knob until the static falls into a low hiss, punctuated with incoherent snippets of music and voices.

Wandering into another room at the back of the house, no windows to let even a hint of light penetrate, I find Ian and another boy placing a teddy bear on an orange plastic chair. A green light glows from under the fur of its chest.

“Do you want to be my friend?” it chirps in a child’s voice.

“The hell is that?” I ask Ian.

“That’s Boo Buddy.”

I spot one of the students I hadn’t met yet standing nearby, but he doesn’t seem interested in an introduction.

The green light fades as red lights pulse to life in the bear’s paws.

“Come play with the bear,” said Ian, invisible in the pitch black. Soon, the red lights disappear too and there is only the sound of our breathing.

“Brrr. It’s cold in here!” comes the high child’s voice from inside the bear.

From the next room, I hear Damian bragging “I got a hug from Alice.”

I smile at the words. As wildly different as Damian is from the kid I was at his age, I can’t help but projecting my own high school desires on him. Cloistered in his room watching YouTube videos, he probably doesn’t think nearly as much of being popular or having a girlfriend, but it’s all high school was for me. And I want it for him. I’m tempted to go in and peek, at least to meet Alice, but I can’t turn myself away from the horrifying stuffed bear.

“Are you playing with Boo Buddy?” asks Ian to the air. “Can you make the red lights come on?” Again, silence, no lights. “Can you make the red lights come on for us, please?”

Nothing.

“Please, make the red lights come on.”

“Do you want to be my friend?” the bear says.

“Make the red lights come on!”

Ian seems strangely agitated.

Suddenly, the sound of shrieking comes from the room with Damian and Caroline. Then the snippet of a song, then the quiet shush of static. I thought for a second. It certainly didn’t sound like Caroline.

“Was that Alice, or the radio thing?” I ask of the shriek.

I wander back that way, and Ian, bored of the bear, follows. Pulling out his phone he shows me a conservative online discussion forum he manages, to which he regularly posts essays on the evils of socialism and liberal identity politics.

Much of the group finds its way to the room. Dave sets up a box that projects a tight grid of hundreds of green laser lights at the walls, to better detect shadows, mists, movements. He and Jody sit on the couch, and Jackson joins them. Ian shows me a photo on his phone of a classic car.

“We got any spirits here?” Dave asks the air.

These outings don’t happen frequently, typically the club works throughout the year at planning, organizing, and fundraising to pull off one trip a semester. The rest of the time they meet in Dave’s classroom to discuss any paranormal experiences they may have had over the course of the preceding week.

The stories that emerge are often fascinating, though Jackson admits “sometimes, in my opinion… not anybody here… but primarily when the freshmen speak it feels like they’re just…”

“Yeah,” groans Ian, “the freshmen are just being freshmen.”

It’s not the only complaint in that vein.

Dave recounts a trip to Ashmore Estates, a crumbling brick building surrounded by neck-high grass two hours away, where a group of freshmen got themselves into a crawl space and worked up to a frenzy in the dark confines, screaming for Dave, insisting that there was a demon.

That trip to the abandoned building, a poor house that served a rural county for the first half of the twentieth century, started off badly. The first time they tried to go, they got twenty miles from the school before the engine started smoking, leaking antifreeze and stinking up the whole bus. They had to turn around.

Trying again the next year, the dash panel of the usually reliable bus “kept beeping, beeping,” says Dave, “and we had to keep stopping and pulling over.”

One of the students suggested that if the bus broke down again maybe it meant they shouldn’t go.

The bus made it.

But the long and ominous trip had some of the younger members rowdy before they ever entered the building. One boy in particular bounded through the place, taunting the spirits to do their worst. He ended up nursing a gashed arm, explaining with a drained face that he had been scratched somehow. Inexplicably. Afterward, Dave booted him from the club.

Then, the crawl space.

“We were all messing down in the crawl space,” Damian recalls, “next thing you know, somebody goes into this back room. She walks out, and next thing you know you hear a loud smack from the room.”

Panic ensues.

“There’s a demon in the closet!” Ian shouts in a mock impression of the girl.

Dave came down and found the girl insistent that it was following her.

“So here I am,” says Dave, “feeling really stupid, talking like Okay, whoever it is, leave her alone, please go away, don’t touch her, stay away.”

After the chaos at Ashmore, senior members of the club began finding ways to weed out some of the others, in part by not telling them the dates of the outings. There are no freshmen tonight.

Caroline speaks so quietly you can barely hear her.

“There’s this room at Ashmore, they say that if you stay in there for a certain amount of time, you get depressed. One guy in our group went in there and said he just started crying.”

Dave mentions a pair of girls that had gone in together, stood in the blackness in two separate corners. They only later realized that both of them had spent the entire time in tears.

“Did you go in?” I ask Caroline.

“No,” she says. Pauses. “I was already depressed.”

“I had an experience in there,” says Damian, “I felt something cold behind me, trying to hold my hand, and it was a child behind me. I did not like that experience of having something there with you. To me it is like… I feel bad for the spirits attached to a place, being there… have no way to move on. I feel sad… being around people that die there. And you can contact something good or bad. That’s why I don’t like Ouija boards. It’s very dangerous in my opinion. I’ve never messed around with one of them, but I’ve seen YouTube videos of them and I think it’s pretty scary. Cause I think about getting possessed by a demon or have the Ouija Board go crazy or have the planchette go in straight circles, which I think I don’t want to mess with.”

“Yeah,” says Caroline, “my dad played with one and it said he would die at 19.”

Hardly seeing either of their faces in the darkness, the stories seem more ominous than they probably would otherwise. I don’t interrupt, but stomp my feet against the cold that’s finally numbing them.

“The one thing is,” says Damian, perhaps thinking again of his grandfather, “you have to say goodbye. So the spirit goes away.”

Hearing him lay out a very specific and precise set of rules makes me smile. I can’t help thinking of Jessie Eisenberg’s character in Zombieland, and the funny contrast of specific, sensible commandments for dealing with something as absurd as zombies.

“Because that’s the one thing you don’t want to do,” he continued, “you have to say goodbye.”

The other rule, he says with equal gravity, is that you should never do it alone.

“Since this is a paranormal investigation,” Jackson practically shouts, breaking the mood, “I would like to say my favorite ghost joke.”

“Oh God,” moans Ian.

“Oh no, oh no, oh no,” incants Damian.

“Wait, wait, wait, hold on, hold on, you guys, you guys, shhhh… I have a joke. What is the difference between a musician and a dead body?”

“Oh, I’ve heard this one,” says Damian.

“One decomposes while the other composes.”

“You told me that one before,” says Damian.

“Yes I did, and you laughed,” seethes Jackson with mock indignation. “What’s a ghost’s favorite meal on Thanksgiving?”

“Ectoplasm,” says Ian flatly.

“The poultry-geist.”

“That one got me,” admits Damian.

Caroline speaks so quietly you can barely hear her.

“There’s this room at Ashmore, they say that if you stay in there for a certain amount of time, you get depressed. One guy in our group went in there and said he just started crying.”

Dave mentions a pair of girls that had gone in together, stood in the blackness in two separate corners. They only later realized that both of them had spent the entire time in tears.

“Did you go in?” I ask Caroline.

“No,” she says. Pauses. “I was already depressed.”

“I had an experience in there,” says Damian, “I felt something cold behind me, trying to hold my hand, and it was a child behind me. I did not like that experience of having something there with you. To me it is like… I feel bad for the spirits attached to a place, being there… have no way to move on. I feel sad… being around people that die there. And you can contact something good or bad. That’s why I don’t like Ouija boards. It’s very dangerous in my opinion. I’ve never messed around with one of them, but I’ve seen YouTube videos of them and I think it’s pretty scary. Cause I think about getting possessed by a demon or have the Ouija Board go crazy or have the planchette go in straight circles, which I think I don’t want to mess with.”

“Yeah,” says Caroline, “my dad played with one and it said he would die at 19.”

Hardly seeing either of their faces in the darkness, the stories seem more ominous than they probably would otherwise. I don’t interrupt, but stomp my feet against the cold that’s finally numbing them.

“The one thing is,” says Damian, perhaps thinking again of his grandfather, “you have to say goodbye. So the spirit goes away.”

Hearing him lay out a very specific and precise set of rules makes me smile. I can’t help thinking of Jessie Eisenberg’s character in Zombieland, and the funny contrast of specific, sensible commandments for dealing with something as absurd as zombies.

“Because that’s the one thing you don’t want to do,” he continued, “you have to say goodbye.”

The other rule, he says with equal gravity, is that you should never do it alone.

“Since this is a paranormal investigation,” Jackson practically shouts, breaking the mood, “I would like to say my favorite ghost joke.”

“Oh God,” moans Ian.

“Oh no, oh no, oh no,” incants Damian.

“Wait, wait, wait, hold on, hold on, you guys, you guys, shhhh… I have a joke. What is the difference between a musician and a dead body?”

“Oh, I’ve heard this one,” says Damian.

“One decomposes while the other composes.”

“You told me that one before,” says Damian.

“Yes I did, and you laughed,” seethes Jackson with mock indignation. “What’s a ghost’s favorite meal on Thanksgiving?”

“Ectoplasm,” says Ian flatly.

“The poultry-geist.”

“That one got me,” admits Damian.

All of it followed me home and gnawed at me in ways I struggled to articulate, which is arguably problematic for a journalist.

There was a lingering sadness and unease when I thought about that night in the house. The teens that came together to wander through rooms in the darkness, clinging to electronic devices with no serious scientific support. Poor teens yelling at spirits until impossible scratches drew blood, attention-hungry freshmen screeching about being possessed, truth-seeking seniors smiling as they stared at copper wires in their hands.

I hated the way I found myself thinking of their efforts in a condescending way, certain it said more about me than them, or maybe more about adulthood than adolescence.

From where I stood, everything they did was ridiculous because there was no such thing as ghosts. And if there were, after thousands of years of people dedicating their lives trying and failing to prove it, what hope did some seventeen-year-old in Springfield, Illinois have?

I know things. In ten years, I will, in all likelihood be at the same job, living in the same house, same wife, same children. But the students have no real idea where they’ll be.

I think of the depression room. Of the girls crying in its corners. Of Jackson making the walk away from it, looking haunted. Of Caroline refusing to even enter it since she had yet to be able to extricate herself from her own unhappiness and could not stand to go in alone and face it. Maybe there was something to Damian’s rules. You have to say goodbye. You can’t go alone.

There had been such a strong sense of isolation in the house. It was unsettling that for as long as I’d been in there, and as small a group as there had been, there were still students I’d somehow missed, perhaps even walking by them unaware in the darkness. At least the one boy I’d seen but not gotten the name of, and then Alice, whose name I’d heard but who I’d not seen.

Trying to wrestle the experiences, pictures, audio recordings into something like a story, I shot Dave a text message to ask who Alice was. A few minutes later my phone buzzed with the reply. I re-read it several times before fully absorbing it.

“She’s allegedly 8,” he replied. “I’ve had psychics say they’ve seen her. No proof however. Conjecture etc. no real proof.”

I was at a loss as to how to feel about the revelation. What to make of it.

Either to validate my skepticism or in spite of it, I tried to dig into the records of the house. In its first days as a private residence, there was never any girl named Alice that lived there. I cross-checked the families of the domestic servants, no Alices there either. Nor Alisons or Elsies or anything else remotely close.

In its days as a Men’s club, no female, least of all a child, would have been permitted to step foot inside.

I was ready to laugh at myself for even bothering to look into it all when I remembered the brief period it had served as a funeral parlor. Despite Dave’s feelings that no ghost would linger in a place like that, I found the years the parlor had operated, then checked the Illinois State death registry against it.

There was a single listing of an eight-year-old Alice dying in Springfield at the right time. Alice Manning, dead in the midst of a polio epidemic on April 10, 1916. Her birthday.

The question of whether or not I believed was actually, as it always is, whether I wanted to believe. To believe meant that Alice’s life hadn’t actually ended so tragically on her eighth birthday. That she lived on. But it also meant that for over a century she’d been trapped inside a dark house, limited to the most fleeting of interactions and human connection.

Going back to the audio recordings I’d made, I caught something I hadn’t before.

When Caroline left, she didn’t just say goodbye, she said “stay here. Don’t follow me.”

Whether I just hadn’t paid attention, or failed to absorb it since it made no sense, I don’t know. But I certainly understood it now.

I guess you have to say goodbye.

PATRICK GLENDON McCULLOUGH lives in Cochecton, New York. His novel Son of the Ripper! was named a Foreword Magazine Book of the Year. Other work has appeared in Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine and McSweeney’s.